Omer Tarin

Omer Tarin

The Sufi poetry of Hazrat Syed Meher Ali Shah, Chishti-Nizami, the Saint of Golra: A brief overview

Pakistan is the land of the Indus River, ‘Sindhu’ or ‘Abasyin’, and as this great river flows from North to South, down to the sea, it runs the length of this entire country. The Indus has seen the growth of many ancient civilizations along its banks and those of its main tributary rivers- the Indus Valley civilization, the Gandhara civilization, and so on—and the land, the long basin or valley of the Indus, has long remained one of the world’s major spiritual-mystical centers (Quraeshi, The Introduction, pp 21-22, 27 and 29). It has nurtured the ancient Hindu Vedantic practice, the Greater Path of Buddhism and Sufi Islam.

By the medieval times, circa 1077 to 1277 CE, Islam had firmly entrenched itself in the Indus region and was home to some of the great Sufi shrines of Punjab and Sindh-such as Hazrat Data Ganj Baksh in Lahore, Hazrat Baba Farid in Pakpattan, Hazrat Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan, Hazrat Bahauddin Zakriya in Multan & etc – which were closely linked and allied to the rest of the major Sufic centers in India (Sharifuddin, p 14). The four major Sufi orders represented here were the Qadriyya, the Chishtiyya, the Naqshbandiyya and the Suhrawardiyya. Of these, the Chishtiyya, or Chishti, had a special link to the masses and probably expressed the most direct and vigorous eclecticism , fusing various elements from local culture and folklore , to the basic and essential Islamic principles as taught by the early Sufis of the Middle East, Central Asia and Afghanistan (the Chishtiyya having originated in Chisht, near Herat, Afghanistan) and utilizing popular music and poetry forms, to spread their teachings (Tarin and Akhtar, p 23 ; and Frembgen, pp 23-24).

Though the Chishtiyya Order had long been established in India i.e. with the initiation of this ‘Tariqah’ or path by Hazrat Moinuddin Chishti, Ajmeri (c 1141-1236) , and had developed and expanded in Central and South Punjab during the time of Hazrat Baba Farid Ganj Shakar (1173-1266/67), it was one later branch of the main Chishtiyya, the Chishti-Nizami ‘Silsila’, named after Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi (1238-1325), that had a major impact on the area of Northern Punjab (comprising the present day Pakistani-Punjab districts of Rawalpindi, Attock and Chakwal) and the nearby Hazara region of the North-West Frontier province (now renamed ‘Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa’ province) and still continues to command a large influence herein; and this impact and influence dates to the time of a later Chishti-Nizami Sufi saint, poet and scholar, Hazrat Syed Meher Ali Shah (1859-1937), of Golra, near Rawalpindi town, Rawalpindi district of Northern Punjab.

According to his biographer, Maulana Faiz Ahmed, Pir Syed Meher Ali Shah was born in a Syed (Sunni) family of Golra village, near Rawalpindi town, in April 1859, and he obtained formal Sufic training under his ‘Murshid’ (guide/mentor) Hazrat Shamsuddin Sialvi, in the Chishti-Nizami branch of Sufism (‘Meher e Muni’’, p 61); and his ‘spiritual descent’ or chain of transmission is appended1.

If we look at the life and teachings of Hazrat Meher Ali Shah (via his own lectures and writings and the writings about him by his contemporaries) we see him emerge as a genuine Sufi saint and teacher of the Chishti-Nizami order, one who lived close to our own times and whose actions and deeds were prominently recorded by the media of that time. We also note the importance of his poetry – in Urdu, Farsi (Persian) and his native Punjabi – in helping spread his teachings to the masses of Northern Punjab and Hazara region (NWFP/KPK), to millions of mostly simple and uneducated people from the rural farming community, as well as other classes and sections of society. In this, his use of poetry as a medium for popular communication, Hazrat Meher Ali’s attitude is very broadly similar to many earlier Chishti Sufi masters; and, yet, it is also uniquely reflective of his own ideas and personal philosophy.

Hazrat Meher Ali wrote in three languages , as mentioned above, and in various poetic forms and styles; he wrote ‘Naats’ (poems in honor and respect of the Holy Prophet Muhammad), ‘Ghazals’ (the traditional Arabic-Persian form) and ‘Nazms’ (traditional longer rhymed verse) in at least three versatile styles i.e. Geet, Kafi and Manqabat. All these styles of ‘Nazm’ are basically for setting to music and for singing (Meher e Munir, p 489) and are quite popular among folk singers and ‘Qawwals’, the traditional musicians/singers associated with Sufi shrines (Meher e Munir, p 489). It is worth noting here that in his metrical restrictions, Hazrat Meher Ali closely followed many of the early Hindi and Persian stylistic elements laid down by Hazrat Amir Khusro (1253-1325), the famous Chishti-Nizami Sufi poet and musical genius who was also a devoted disciple of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi – we thus see many of Hazrat Meher Ali’s Persian and Punjabi verse laid out according to a rigorous system of Raaga-oriented methodology ; and it was this format which enabled many folk singers and Qawwals to so easily adapt his poetry to popular use, and to spread it far and wide in the Northern Punjab region and its environs (Meher e Munir, pp 490-495 for various details) and which also allowed the masses to memorize these (and the lessons/teaching /messages therein) and to propagate them further (Tarin and Akhtar, p 28). The tradition of singing such spiritual messages and teachings, either with the help of musical instruments or with the voice alone, had long been common in the Indus valley region, from pre-Islamic times and had always been popular among the people of all classes and creeds; and it lies chiefly to the credit of the Chishti Sufis, over the ages, that they were able to adapt and utilize these ancient folkways to their own unique purposes.

We therefore see that (a) Hazrat Meher Ali Shah was able to continue and keep alive various old Chishtiyya Sufi poetic-musical precedents from the 12th century CE, down to modern times, in an ongoing progression that fused the Sufis special love and compassion, with his personal philosophical approach, his own ideas; and (b) in thematic terms, write poetry that was powerful, beautifully expressed and highly eloquent on several topics, which were very relevant to his own beliefs and which proved to be very influential over a vast spectrum, over time (Meher e Munir, p 492).

Hazrat Meher Ali Shah’s Persian and Urdu poetry, including many of his Ghazals are not so popular anymore; but his Punjabi poetry, especially his ‘Naats’ for the Holy Prophet (saw) and his ‘Nazms’, set to music and song, continue to be immensely popular even today. Some of his Punjabi poetry (written in the typical Northern Punjabi idiom) – for example, his famous Naat, ‘Kithe Meher Ali, kithe teri sanaa’, are known far beyond the borders of Punjab, or Pakistan, and have attained a truly universal Sufic recognition; and are part of the repertoire of world-renowned singers such as late Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and diva Abida Parveen2. The most significant aspects or features of this fine Punjabi poem and of some other Punjabi poems like ‘Dil lagra beparwawa naal’ and ‘Laya mehndi khoon ajal di’ (a Punjab marsiya dedicated to the martyred grandson of the Prophet, Imam Hussain ibn Ali) are:

Hazrat Meher Ali’s view of Allah/God as the Beloved and Beneficent One, from whose Divine Creativity sprang forth all Creation, everything in the universe- a view closely linked to the concept of ‘Wahdat al Wujud’ (Unity of Being/Existence) yet, still making a fine distinction between Creator and the created; like Hazrat Mohyuddin Ibn ul Arabi, the earlier Sufi sage of Murcia, Spain, he also sees all Creation as ‘borrowing’ their being(s) from the Creator’s Essential Being, and eventually ‘losing’ themselves in that Source.

Hazrat’s views about the utility of poetry, music and ‘Sema’ (the traditional Sufi audition practice, which we have seen, was much-developed by the Chishtis in the South Asian subcontinent) as a main component of Sufic teaching/training methodology and his lyrical expression inspired and crafted, to ‘move’ the auditors at various levels : the masses to a basic emotional shift and the more ‘exclusive’ Sufi trainees/disciples attached to his Khanqah/school, to a mystical state whereby a perception of ‘Fanaa’ (Annihilation into the Divine Source) could be had i.e. a ‘dying in life’ experience, under controlled circumstances, as advocated as far back as the 11th century CE by the likes of the early Sufi sage Hazrat al-Hujwiri ‘Data Ganj Baksh’ (Kashf ul Mahjub, Part Last: the 11th Veil).

Hazrat’s special, deep veneration and love for the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw), expressed time and again, in mystical language and splendid imagery – viewing the Holy Prophet not only as just a human prophet, but a special and unique being, the ‘Insaan e Kamil’ (the Ultimate/Perfected Man) from whom all the Grace and blessings of Allah/God, are channelized. It is especially significant that, as such, Hazrat Meher Ali clearly stresses that the Holy Prophet is a unique exemplar of living for Muslims and is above all human, earthly criticism.

Now, when we come to view these basic premises, in terms of their later influence, we see that, during and after his life, Hazrat Meher Ali Shah-sahib’s verse became ‘appropriated’ by two separate and even divergent streams of Muslim/Islamic thought. Art, literature, are shaped by the creative imagination but how people interpret or understand, or even appropriate, such works, is an entirely different matter. In this case, we see the appropriation of Hazrat’s literary work by:

(a) The Sufis proper, especially the Chishti Sufis of (now) Northern Pakistan, and indeed, all of Punjab and even beyond. This group maintained, as always, over the centuries, the typical, eclectic and broadly-humanitarian approach ; adopting the mantle of love, individually and collectively finding themselves in a special mystical communion with Allah/God and all Creation, and with the Holy Prophet (saw) and his ‘Sunnah’ (deeds/practices), and as always channeling these connections via the media of poetry and music (folk and Qawwali/Sema) – for them, Hazrat Meher Ali was a poet in the finest Sufi tradition, part of an ongoing stream or flow that has always been there for everybody.

(b) The pseudo-Sufis and/or other ‘Islamist’ groups which, whilst not fully accepting Sufi practices, wished to obtain some of the popular benefits/sanctions attached to Sufism (in particular Sufi poetry and music) for their own ends, for self-propagation. Sadly, some of these groups, during the late 1920s and 1930s onwards, to present times, have chosen to focus on rather narrow and negative perspectives, creating internal schisms and sectarianism in Islam, and in post-Independence Pakistan, in abusing a true and rightful mystical-poetical tradition for the sake of marginalizing and condemning people of all creeds .

In addition to these two separate groups, today, both ‘owning’ Hazrat Meher Ali Shah’s message and art, we can also see that, historically, during Hazrat’s later life, some of his ideas were also utilized skillfully by the Pakistan Movement and the All-India Muslim League leadership in Northern Punjab, circa 1920 onwards, in ‘inspiring’ the ‘welding’ of a ‘Muslim identity’ (Meher e Munir, p 297 etc ); indeed, we know from Hazrat’s correspondence, held at the Meheria Library at Golra Sharif shrine, that many prominent Muslim leaders of the Punjab were in contact with him at various levels, from at least 1922 to 1935. Apart from Allama Sir Muhammad Iqbal, the national poet of Pakistan, who wrote to Hazrat to understand aspects of his verse and to clarify various mystical concepts; we also have examples of correspondence with politicians and statesmen such as Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan, Malik Sir Khizar Hayat Tiwana, Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani, Sardar Muhammad Ali Gheba and several ‘Sajjada Nashins’ (custodians) of important Sufi shrines, who held political ambitions. It is not unusual that such prominent political figures might want to court a popular saintly personality with such an exceptional body of literary work, even though he himself eschewed politics and political ambitions.

Hazrat Meher Ali’s shrine at Golra still remains a focal point in Pakistan, for people of all shades and opinions and his poetry and songs, continue to be part of the historical cultural heritage of not only Northern Punjab and environs but all of Sufi Islam in South Asia, a gift of the Indus.

I. Notes:

1 Descent of Pir Syed Meher Ali Shah (‘Meher e Munir’, pp 475-76)

The Holy Prophet Hazrat Muhammad, Rasul Allah (saw)

↓

Hazrat Imam Ali (ka)

↓

Hazrat Hassan Basri

↓

Hazrat Abdul Wahid bin Zayd

↓

Hazrat Fudhayl ibn Ayaz

↓

Hazrat Sultan Ibrahim Balkhi

↓

Hazrat Sadiduddin (Huzaifa al Maarshi)

↓

Hazrat Aminuddin al Hubayra

↓

Hazrat Mumshad Alvi (Dinawari)

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Abu Ishaq Shami, Chishti

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Abu Ahmad Abdal

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Abu Muhammad

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Nasiruddin Abu Yusuf

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Qutbuddin Maudud Chishti

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Sharif Zandani

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Usman Harooni

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Moinuddin Hassan Chishti, Ajmeri ‘Gharib Nawaz’

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki

↓

Hazrat Baba Farid ud Din Masaud ‘Ganj Shakar’

↓

Hazrat Syed Muhammad Nizamuddin Auliya ‘Mahbub I Ilahi’ (Chishti-Nizami branch starts here)

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Naseeruddin Chiragh Dehlvi

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Kamaluddin ‘Bande Nawaz’

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Sirajuddin

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Ilm ud din

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Mahmud Rajan

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Jamaluddin Juman

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Hasan Muhammad Nuri

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Shamsuddin Muhammad Chishti

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Yahya Madani Chishti

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Kalimullah ‘Wali Jehan’

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Nizamuddin Aurangabadi

↓

Hazrat Khwaja Fakhruddin ‘Fakhre Jehan’

↓

Hazrat Shaykh Nur Muhammad Maharvi

↓

Hazrat Shaykh Suleman Shah Taunsvi

↓

Hazrat Shaykh Shamsuddin Sialvi

↓

Hazrat Pir Syed Meher Ali Shah, Chishti-Nizami, of Golra

2 For Abida Parveen’s fine rendition of Hazrat Meher Ali Shah’s Punjabi poetry: http://folkpunjab.org/abida-parveen/kithe-meher-ali-kithe-teri-sana/

II. Works cited:

- Ahmad, Maulana Faiz. Meher e Munir. Urdu biography of Hazrat Meher Ali Shah. Lahore: Pakistan International Printers, 1973

- Al-Hujwiri, Hazrat Ali bin Uthman al-Julabi ‘Data Ganj Baksh’. Kashf ul Mahjub. Orig ‘Revelations of the Veiled’, in Persian, c 11th c. English translation by Prof RA Nicholson, 1911.

- Frembgen, Jurgen W. Journey to God: Sufis and Dervishes in Islam. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford UP, 2008.

- Quraeshi, Samina. Legends of the Indus. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford UP, 2017. Orig .pub by Asia Ink, 2004.

- Sharfuddin, Dr KM. Pakistan mein Ziyaraat e Sufiya, eik jaeza. Urdu, ‘Sufi shrines in Pakistan, an analysis’. Lahore: Ghausiya Press, 1956.

- Tarin, O & Akhtar, Z. ‘The Chishti Sufi Order in Pakistan – an Historical Analysis’. In Sungut; Journal of the Humanities. Lahore, Vol XXXV, No 2, 1999, pp 21-32.

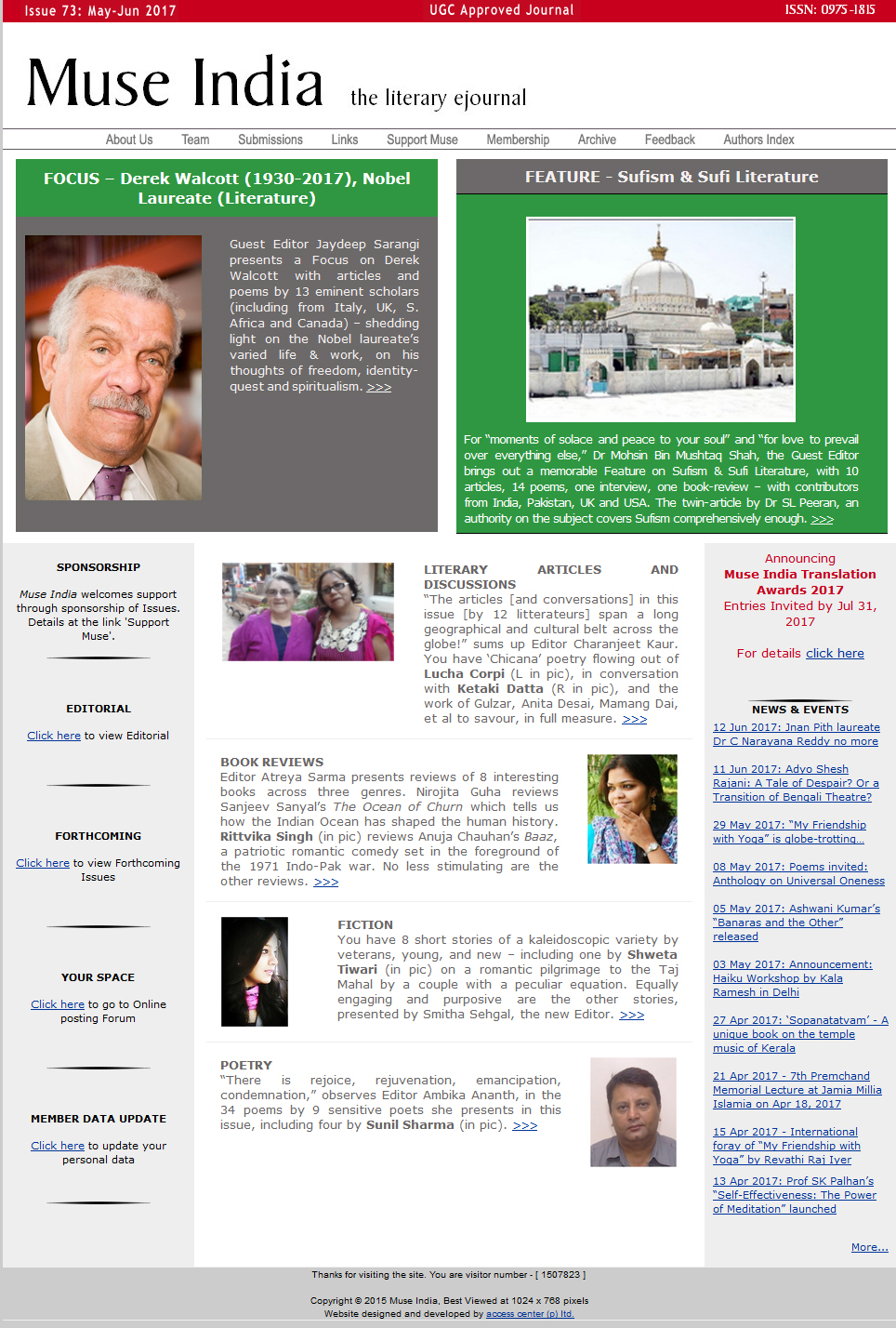

Issue 73 (May-Jun 2017)

-

Articles

- Mohsin Bin Mushtaq Shah: Mir Syed Ali Hamadani

- Omer Tarin: Sufi Poetry of Hazrat Syed Meher Ali Shah

- Romy Tuli: Baba Bulleh Shah and Walt Whitman

- Sat Paul Goyal: Jelaluddin Rumi

- SL Peeran: Sufism – Islamic Spirituality

- SL Peeran: Who are the Sufis? Who are the Faqeers?

- Sudeshna Kar Barua: Jalal ud-Din Muhammad Rumi

- Syed Habib: Spirituality – The Crown of Kashmir

- Syed I Husain: Nothing is Sacred Anymore

- Usha Akella: Harmony is the Flour, Love is the yeast

-

Poetry

- Aiman Peer

- Anum Ammad

- Divya Garg

- Fareeha Manzoor

- Kainat Azhar

- Myra Edwin

- Omer Tarin

- Rajorshi Das

- Umar N

- Usha Akella

-

Interview

- U Atreya Sarma: In Conversation with Mukunda Rama Rao

-

Book Review

- Mohsin Bin Mushtaq Shah: Song of the Dervish

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Editorial