Preeti Parikh

Photo credits: commons.wikimedia.org

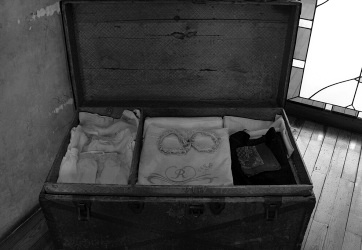

SANDOOK | THE TRUNK

The Colonel’s wife—next-door neighbor and spouse of my father’s commanding officer— kept a trunk in her kitchen: black, wooden, her husband’s name stenciled on in white. Often at lunchtime, she’d open the trunk and pull out a bin of dried fish—a pungent missive from her mother’s seaside home. From those desiccated clumps, she’d pick a morsel, hold it out for me to smell, then slip it into the boiling stew. I’d prance about, recounting the stories I’d been reading, how a class of girls had the best adventures at a boarding school in a faraway land. She’d listen intently, then tell me about her sisters, how when they were girls, their mother would unbraid their long black hair, massage their dry scalps with warm coconut oil. In the common verandah, I’d watch her newborn pup—sable-coated, milk-dazed, tottering. I’d ask her, cruelly and often, why she did not have any children. That’s just the way it is, she’d reply each time. One afternoon, when the regiment was away, stationed for months at a remote training camp, I noticed her, solemn, gazing out the window at the sweet pea blooms, the bamboo trellis, the Kanchenjunga glinting its steely white angles through distant muslined clouds. Up on a landlocked hill overlooking military training grounds was her barrack home. With her, in the heart of those tin-roofed temporary living quarters, was the Colonel’s black trunk.

Decades later, one frantic evening in my Midwest American kitchen, impending soccer scrimmages and dance practices loom large as I rush to cook the family dinner. Amidst my fumbles with the pots on the gas stove, the khichdi-filled pressure cooker hisses, then pops. Bursting open, its lid leaps at me. The scalding contents spew a turmeric-stained mash that plasters the countertop, the black cabinets, the ceiling. Numbers flash yellow on the microwave clock. Bits of rice and green lentils—plosive—burn my forearm. I think of the children—upstairs, removed—the elders rustling in the adjacent room. On the tv, news from the homeland mourns a female body—Beti: a daughter pawed, raped, eviscerated. What feeds us that wants us, I wonder, how deep its hunger, how rancid its famine? The bright horizon beyond the window and storm door fades crimson, orange, pink. I scoop up the spills, wet some rags, climb the three-step ladder and get cleaning.

(Note: Khichdi – an Indian dish of rice and lentils cooked with mild spices.)

OF THE [ ] | CINEMA

Bhagwaan ke liye, mujhe jaane do, For the sake of God, let me go, the hapless heroine pleads as she clasps her pallu to her bosom. For the sake of God, please. This, from the movies of your childhood that depict garish villains pulling at women’s sarees, attempting to disrobe them. Nahein, the woman wails. A montage of slithering ankles and writhing necks, and she reappears on screen, disheveled, her saree unwound blouse torn, kajal smeared, scratch marks on her chest, arms, and back. Shame-faced, she’s ready to end her besmeared existence. Sometimes this sad conclusion is avoided when the muscled hero intervenes in the molestation and stops his antagonist just in time. Vanquishing his foe, he then valiantly offers the poor maiden his coat/shirt/shawl to cover herself. If it is not already established in the narrative that he is her brother/father/son, you can predict with a nearly hundred percent accuracy that she will fall fall in [ ] with this manly savior.

You want | to [ ] this [ ]

You want | [ ]

You want | as if

( Notes: Pallu – loose end of a saree draped over the shoulder; Kajal – traditional eyeliner used to create a dramatic, black-rimmed eye look.)

OF THE BODY | WOMAN AND [ ]

(After a painting by Raja Ravi Varma)

Twisting your waist

and holding on to your sakhi’s shoulder,

you lift your left foot

pretending

to remove something

impregnated in your sole:

a thorn perhaps

a sharp pebble

a hunter-king’s heart?

Leaning your head back

you glance out of the frame

past your adoptive father’s hermitage

by the Malini river—

the search a familiar gesture

relic of your abandonment at birth.

You yearn for some knowledge

novel to you

but old as the earth

old as the protection

of the shakunta birds

you were named after.

Jagged, haggard

yet made new each time:

a bow, an arrow

a coveted deer

a forgetful king

a myth that exonerates him in each retelling.

Shakuntala, girl,

damn, are you still looking for Dushyanta?

(Notes : Sakhi – female friend or companion; Shakunta – type of bird referred to in old Indian texts, probably blue bird; Shakuntala – heroine in the ancient Sanskrit play by poet Kalidasa, who fell in love with King Dushyanta; Dushyanta – king of the Chandravamsha dynasty.)

Issue 123 (Sep-Oct 2025)

-

EDITORIAL

- Semeen Ali: Message

- Yamini Pathak: Editorial Note

-

POEMS: MATWAALA POETS

- Anu Mahadev

- Gitanjali Lena

- Kashiana Singh

- Mayur Chauhan

- Megha Sood

- Pramila Venkateswaran

- Preeti Parikh

- Sara Garg

- Shadab Zeest Hashmi

- Shikha Malaviya

- Shlagha Borah

- Uma Shankar

- Usha Akella

- Varun U Shetty

- Vivek Sharma

- Yamini Pathak

- Zilka Joseph