Amiya Sen

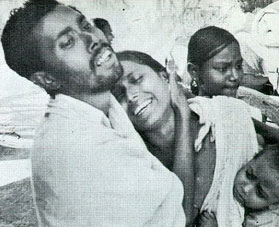

Refugees during Bangladesh liberation war, 1971. Credit- weebly.com

[This is an extract from Amiya Sen’s nonfiction book-length account of refugees from East Pakistan who had been rehabilitated in Dandakaranya, a region that includes parts of Chhattisgarh, Orissa and Andhra Pradesh. The Dandakaranya Development Authority was created by the union government in 1958 to assist refugees from Pakistan.]

Dear Su,

...I had no idea about Dandakaranya. After crossing a hundred and forty-five miles of hilly terrain between Mana camp and Raipur we reached Kondagaon--high above the plains. Yet, even at that point, I didn’t realize we were at the forest’s gate. This was the entrance to the heart of the Dandakaranya project. I had imagined the real Dandak forest lay deeper inside. This was a dense settlement of thousands of people--little Bengal, just like little Andaman.

Jogani astounded me. This was the first planned village as part of the project, about six or seven miles from Kondagaon. In July 1959, the village of Jogani was established with 88 families and a total population of 392.

Although we are now urban dwellers on a mass basis, the image of a village is well etched in our hearts. It is rare to find an individual who hasn’t seen a village or lived in one for at least some time. But what a village this was! A few drab-looking tin houses sat in an area cleared off the forest floor. No other human settlement was visible through the gaps of the scattered shaal trees lining the nearby area.

A few broken houses dotted the landscape. Many of those rehabilitated here with government aid had already left the village. Jogani’s land is sterile; it doesn’t cultivate any edible crop. I was told that only two or three families had been lucky enough to receive arable land. The rest of the land was left unclaimed at the time of my visit. Those who left the village didn’t do so without giving a fight to the infertile soil. Along with their menfolk, women too had taken up crowbars to rid the soil of shaal saplings and weeds. For days on end, many of them ate grass seeds to curb hunger. At last, helpless and defeated, they drifted off this settlement.

There is soil-testing laboratory in Jagdalpur, Madhya Pradesh. Apparently, all peasant refugees are allotted land only after the soil is tested in that lab. But Jogani tells a different story--it doesn’t seem like the soil of this village was ever tested. This could be the first step of an experiment with agriculture-reliant refugees.

Those who have stayed back in the village depend on jobs or labour. Take Jaladhar Sarkar, for instance. He came to India in 1954, from Bishwambhapur village in Srihatta district. After living in a camp for four years, he has been rehabilitated in Jogani with twenty-one bighas of land. He and his two sons support a family of six or seven by working as peons and construction workers. The land they received lies fallow and unused.

In 1960, a loom had been opened in Jogani. It still exists but has lost its sheen. Work goes on at an irregular pace. Whenever the products made there accumulate, there is a pause in the work of daily wagers.

Currently, the only employment generator around Jogani is Borgaon Industrial Centre, about four or five miles from the village. Men and women from Jogani walk every day to work there. Among them, the daily wagers are the most disadvantaged. The work, low-paying as it is, doesn’t come with the guarantee of being available all through the year.

...

It was a Monday. The village, if one could call this desert-like place that, looked totally deserted. Besides shaaland mahua trees, there was no sign of green anywhere. Not even a pumpkin or bottle gourd patch that one saw in Mana’s camps. Mana has water, it has canals and ponds. Here, tube wells exist. Had paddy or any other crop grown on the land, the villagers would have pumped out water to cultivate some vegetables. But where is the time for that now! Every morning they must run to Borgaon in search of work. If only that could fill their bellies! But then, it’s possible that that the soil here is indeed barren.

I met a few people--none of them evinced any joy on having received land and a house for free. Actually, they got the money for their houses as a loan, which they needed to pay off once they were settled. But what settlement and what pay-off? With no place to go, they continue to stay here, in spite of all hardship. But they are not un-enterprising. They toil hard to make sure their children receive education. They would take up any work that comes their way. But the opportunities are so limited.

The very first step of the Dandakaranya settlement left me disappointed. In comparison, I was pleased to see Bijapur as part of my present trip. This was situated in Bastar too, but as a transit camp, not a village. As of March 15, 1965, 67 families stayed there.

There were only two tube wells in the entire camp. But a spot of green welcomed one to every hut. Bottle gourd and pumpkin vines climbed up the roofs of huts. Mounds of mahua flowers were spread out to dry in front of several houses. These would be boiled to make jaggery. This settlement was forest-dependant too. But the dense cluster of huts and the camp’s consistent population had imbued it with a lively atmosphere. The camp dwellers effused optimism. They dreamed of ascending to a better life -- of farmland, house, agricultural loan, and the victory roll of produce brushing against plough.

Life is at work, everywhere. Saplings pierce cracked walls to sprout. Flowers bloom on mountain tops. I have even seen fish germinating in the city’s makeshift drains.

I enter a hut and find a young mother carrying her infant on her lap. It’s her first born. The young father, though excited, is also a bit distressed. Nights in Bastar are still quite chilly. The child doesn’t have any warm clothing. In many homes, I saw just kanthas and pillows for bedding. No one has quilts or blankets. Almost all these people arrived in India following the 1964 riots in Pakistan.

In an instant, that cabinet stuffed with blankets in Mana flashed before my eyes.

I ask the refugees, “Didn’t you get any blankets?”

“No, didimoni,” say the men and women in unison. “We only got woks, enamel plates, a bucket and a few such things. These were given to us in Sealdah station. We didn’t get anything after coming here.”

“You all came here through Mana, right?”

“Yes, didimoni.”

The path to enter Dandakaranya is through Mana—the headquarters of all transit camps and work centres of the project.

According to government statistics, refugees over the age of eight are provided sixteen rupees or clothing worth that amount. The record doesn’t mention how many times this happens; possibly only once. The record also notes the distribution of blankets.

“Woollen blankets may be supplied at the rate of one blanket per adult, subject to a maximum of three per family.” [Estimates Committee, (B.C. No. 412) 1964-65]

The blankets were meant for last year’s riot victims. These refugees belong to the same category. Why didn’t they get the blankets then?

The dole money the refugees receive isn’t enough to cover even two square meals a day, let alone allow for clothes. But leave aside government funds and statistics; the stash I saw in Mana came mostly from donations meant for refugees. If those blankets don’t come to these unfortunate people, have they been filled in almirahs just for the purpose of being displayed to VIPs?

In Mana, expecting mothers received yet another benefit. When a baby was born, the mother and her child got a set of new clothes. The women of Jogani aren’t as fortunate.

A gentleman accompanying me said, “Don’t believe everything they say. These people here are no less sly; they might have sold off the blankets.”

I know it is easier being the devil than the lord. But looking at their faces, it appeared improbable that so many male and female devils had landed here from East Bengal.

For argument’s sake, even if one accepted the gentleman’s proposition, the question remains as to why these people sold off the blankets. One can discount those who have left the camp. But those who have stayed back know very well how indispensable blankets are during winters here. They are also aware that it is impossible for them to find any alternative sources of combating the cold weather. If knowing this, they still sold off the blankets, it follows they must have done so out of extreme penury.

The British robbed India to add riches to its empire. And we have robbed our own poor of food and shelter--in the name of freedom.

Issue 55 (May-Jun 2014)

-

Essay

- Archna Sahni: Machu Lobsang

-

Translations

- Amiya Sen: 'Aranyalipi'

- Jatin Bala: Life in Refugee Camps

- Smritikana Howlader: The Song of the Refugees

-

Critical Articles

- Aatreyee Ghosh: Passive Bangalee Bhadralok

- Deblina Hazra: Prafulla Roy’s novels

- Subashish Bhattacharjee: Narayan Sanyal’s Partition Trilogy

-

Conversation

- Manoranjan Byapari: In Conversation with Jaydeep Sarangi

-

Book Reviews

- Anand Mahanand: ‘The Wheel will Turn’

- Rob Harle: ‘The Wheel will Turn’

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Editorial