Swati Chawla

Three Mini Stories

1. I Re-Member

A professor very fond of the word "etymology" was telling me the route to her house. That is where the re-membering began.

I re-membered the tikozi-- didn't know what it was called in English. My nani used it. They had a kettle. One with a long neck--a long curled neck. Wisps of steam would rise out of it in perfect white curls every time nani poured tea and put the lid on. Then she covered the kettle with a tikozi and called us to the table. Chai thandi ho jayegi. Jaldi aao. The tikozi had on it a girl's perfectly balanced pirouette, and rose flowers. It was conical and it folded neatly. It had to be dry-cleaned.

My nana-nani are dead now. The house they built, with its garden in which they kept the tea table also got re-membered. My mama sold it off. My widowed masi who stayed with nani, despite my mama's attempts to re/de-member her, moved into his new house. She took the tikozi along. I hadn't known.

At my professor's house. She made some Chinese tea and put it in the kettle--nanima wallah kettle-- to "brew", a verb I had not encountered in action before. And lo and behold-- as my Eng Lit prof is fond of saying in exclamation-- she pulled the tikozi out. (To assist the "brewing" I presume.) I said, "You have one of those! My nani had one. What is it called in English?"

Tikozi.

Spell it.

Tea and cosy, she said. (It had been an English word all along.) Some remnants of our colonial past that I like to preserve, she said.

(Oh, it is actually English then?)

I asked my masi if she knew where one could buy one of those. She said she might still have my nani's.

But don't you need it?

No, no one uses them anymore.

Give it to me!

The tea cosy, having found a spelling, is now re-membered on my dining table. Some remnants of my colonised memory that I like to preserve.

2. Profeacher Papa

Dear Aakangshita,

You never liked this name. I haven't used it myself these ten years, and this is my last letter to you.

Your name was not the first thing your mother and I couldn't agree upon. I had had no problems being Chandrabhushan Pratap Malik but she felt most names I suggested had a few syllables too many, and you would take needlessly long while filling up forms.

Being Aradhana, she felt that Aakangshita would similarly inconvenience you, making you the first one to be called in at every interview. I gave up the idea of naming you with the first letter of the alphabet. Indeed, the first letter of every alphabet I had learnt.

I read in your interview yesterday that you are a Beatles fan. I had met John, you know. And Ringo. But that was then. Then--when I didn't attend your Parent-Teacher meetings because you felt embarrassed. But I used to glance through your notebooks. I was glad you had none of my faults.

They asked you what you would have been if you hadn't been a writer. You said you had always wanted to teach. That's not true. Not entirely. Even before you wanted to be a teacher, or a "profeacher" (oh...Papa is a professor, but I want to teach, you would say!), even before that you had wanted to be a truck driver. You leapt out of the car at a red light one day and pointed to a truck next to us: That's what I want to be! Trucks are high and mighty and fun, you said. Think of all the places you can go to, I told you. I had gone all over the country hitchhiking on trucks. The drivers were the most generous and free spirited people I have ever met. I wished the same for you. Your mother steered you towards becoming a pilot.

They asked you what you learned from father. Travel Tips, you said! Your mother paid for everything when you first went abroad. I could offer my experience: Go with an open return ticket. And never take more than you can carry on your person.

You chose to not carry my surname. The world knows you today by your mother's name and the name your mother gave you. I am glad that they knew you.

Aakangshita, I am sorry I went with an open return ticket. I am sorry I never returned. I couldn't carry my grown up headstrong child on my person. But that was then too.

I am coming back home.

Papa.

3. Dal ka Halwa

Badima was only sixty when she became a grandmother. Since "dadiji" sounded awfully like the "mataji" she had been subjected to in DTC buses, we were instructed to call her "badima". After mummy died, badima took it upon herself to teach me to cook.

We had graduated to dessert. First up was sooji ka halwa. I was pouring ghee along the circumference of the kadai. (Badima could never have enough ghee.) Hor pa, hor, utte pa. Asi koi bangali madrasi thodi haige aan? Koi kameen e?

We are not Bangali-Madrasi. Important lessons those, and words of subtle caution: the Bengali boyfriend, and the palate that craved idli-sambhar were unacceptable.

I don't like sooji halwa, I told her. Could she make dal ka halwa? Of course she could. But I had never seen her make it...? That was because she hadn't made it for a while. For how long? Batware ke baad. Since the Partition. But that was 60 years ago! If she hadn't made it for 60 years, surely she didn't know how. Admit it! Badima was never one to concede defeat. I persisted:

Kyun? Yahaan dal nahin milti? Ya ghee nahin milta? Ya cheeni?

Dal ka halwa was the last thing she had eaten in Sargodha before setting off for Delhi. She loved it, and had had a little too much. She didn't get her period for six months.

But the halwa had nothing to do with your period, I told her.

No use. Sooji halwa it was.

Last summer, I was invited to organise discussions around Nehru's Discovery of India for school children. It was tough persuading badima to take the session on Partition. But what will I tell them? I don't know much of Gandhi-Nehru and azaadi. The school kids these days know so much more! Just tell them what you do remember, I told her.

As it turned out, the kids were not interested in Gandhi-Nehru-azaadi either. They asked her if she had gone to school. She had. How old was she when she got married? 19. Had she met dadaji before? No. How much did gold cost then? 25 rupees a tola. Then why didn't she buy 2-3 kilos? Badima quipped--kal ko tumhare pota-poti tumse poochenge. Tumhare zamaane mein 25 hazaar ka tha? Toh 2-3 kilo le kar kyun nahin rakh liya?

The session ended and I took her to the office to sign for her conveyance and honorarium. At 81, this was the first time her labour had been rewarded in cash. Two thousand rupees. That was the sum her father had given her when she left from Sargodha. That was all the money they had. She was the eldest among the children, and he would be coming in a week's time. She had lost the money. Or had it been stolen on the train? Her father didn't come the next week. Or the week after. He didn't come for six months.

Back home, my grandfather teased her. She had her first kamaai. Where were the sweets? I volunteered, "sooji ka halwa?"

No, Badima said, it was time for me to learn another dessert.

Issue 42 (Mar-Apr 2012)

-

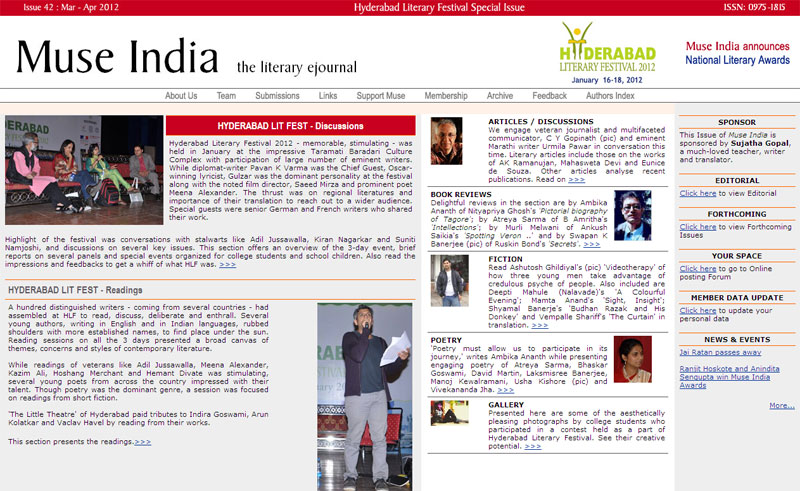

'Death be not Proud’ : Tributes to Masters

Readings by The Little Theatre group- Indira Goswami : Short Fiction ‘The Empty Chest’

- The Little Theatre : Tributes to Masters

- Vaclav Havel : Excerpts from the Play ‘Largo Desolato’

- Poetry Reading

-

English

- Aditi Rao

- Ajay M Konchery

- Amrita Nair

- Anindita Sengupta

- Arjun Chaudhuri

- Charanjeet Kaur

- Hoshang Merchant

- Kazim Ali

- Kumarendra Mallick

- Meena Alexander

- Nabina Das

- Navkirat Sodhi

- Prageeta Sharma

- Robert Bohm

- Santosh Alex

- Semeen Ali

- Sridala Swami

- Sushmita Sadhu

- Regional Languages

-

Bengali

- Angshuman Kar

- Mandakranta Sen

-

Hindi

- Ahilya Misra

- Kishori Lal Vyas

- Rishabha Deo Sharma

- Shashi Narayan Swadheen

-

Kannada

- Arathi HN

- Mamta Sagar

-

Maithili

- Udaya Narayana Singh

-

Malayalam

- Ajith Kumar

- Anitha Thampi

-

Marathi

- Hemant Divate

-

Telugu

- Chennaiah V

- Gopi N

- Raghu S

- Raja Hussain

- Sailaja Mithra

-

Urdu

- Ashraf Rafi

- Hasan Farrukh

- Masood Jafri

- Mushaf Iqbal Tausifi

-

Urdu Mushaira

- Elizabeth Kurian ‘Mona’ : ‘Peshe Khidmat Hai’

-

Fiction Reading

- Priti Aisola

- Sagarika Chakraborty

- Srilata K

- Sudha Balagopal

- Swati Chawla