Anjali Purohit

Anjali Purohit

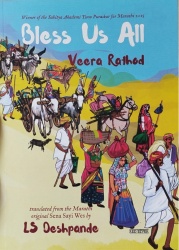

Bless Us All | Veera Rathod | Translated by L S Deshpande |

Poetry | Red River Press | ISBN: 978-81-976304-9-1 |

Paperback | Pp 116 | Rs. 299

Bless Us All is the English translation, by L S Deshpande, of Veera Rathod’s Marathi book of poems, Sen Sai Ves.

Rathod’s poetry gives voice to his people, the Lamaan Banjara, who carry their homes on their backs and whose land is their caravan—they are historically pastoralists, breeders, traders, transporters of goods through difficult terrains, forests, deserts and mountains.

His verse traces the precarity of their existence, the depletion of their resources and livelihood and the erosion and worsening of their social standing. Rathod brings into sharp focus the wrongs historically committed upon the community—be it by the British rulers who had legally “notified” them under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, thereby branding every Banjara a criminal at and by birth, or by independent India, which, post-1947, still took five years and sixteen days to declare them “denotified”:

…that was the story of the days,

When our parents, relatives,

Kith and kin were dropped

From the list of humans…

…we won our freedom

on 31st August 1952…

…There were weals left on our bodies

even after the country’s freedom.

The barbed wire of the settlement

compound was tightened…

… Before we’re born,

they write on the mother’s embryo:

‘A thief, a criminal, an adulterer,

a trader in flesh …

Economic deprivation, the lack of formal education and a peripatetic existence, coupled with the burden of societal mistrust, have kept much of this nomadic community in hardship and penury.

…The houses with the sun overhead

and the mind, a battlefield of innumerable questions —

and people set out in a daily funeral procession.

The exquisite, dreamy picture of hunger and bread

is never dismissed from their eyes.

Which Nirmik drew this not-to-be-crossed line?

None dared cross it.

The way passed through the forest —

epoch after epoch.

It’s a fatal journey with chained legs.

The piteous call in the midst of an uproar wasn’t audible.

This is an era when men are auctioned.

There’s the tradition that carried the flood of humanity.

We see here a caravan of mute agonies

carrying a begging bag

on the way through the forest…

While Rathod’s poetry reflects the community’s full range of grief, distress, disappointment and outrage at injustice, it is significant that he never gives in to bitterness. He writes of how songs of hope have given his people strength. He speaks of his mother, who has poured her story into the grinding wheel— day and night pounding her pain into the flour: “We have been raised on the flour that has come from this grinding stone”, he asserts, when the storm crushes her dreams, the sparrow rebuilds her broken nest. Whatever hellfire the sultanate of the sky wrecks, the soil never dies! This belief in the fundamental resilience of life is reflected in the way of life of the Banjara people: in their songs, their dance, the colours of their embroideries, traditions and customs, the peacock tattoos on their bodies, the mirrors that reflect a myriad hues.

With the erosion of their traditional means of livelihood, the Banjara’s roles have been debased. In the past, the Pardhis were hunters, the Kolhatis, dancers, Vasudev performed devotional songs, the Gondhali bestowed blessings, and the Bahurupiya performed as a woman or eunuch. But now:

…A theft is committed:

Get hold of them,

handcuff them,

the Pardhis.

Thieves, dacoits must be arrested….

Kolhati’s Rangi

used to dance

to feed herself.

Now, she goes to work

and they call her

a whore!

Wasudev’s Pirya

and his son

are rotting,

in God’s name

and by God’s name…

…Gondhali performed the pooja…

But he forgot to do it

for his house, his family

and his children.

Bahurupya’s Mahadya

got his sex transformed,

simulated the eunuch,

became one himself.

Though a father of two children,

people called him names…

Yet we are not reckoned as humans…

…our entire community.

When shall we be received as ‘humans'?

When will our beloved government

issue a certificate to that effect?

Despite the deprivation, exploitation and grave injustices they have endured, the prayer of the Banjara is for the well-being of every living thing—man, woman, child, beast, plant, bird or insect. This is the prayer— ‘Sen Sai Ves’ (Bless Us All)—that titles the book.

What most saddens and enrages Rathod is the exploitation of their poverty and precarity to sexually use and abuse women of the community. His poems on this issue are deeply unsettling. He speaks of the celebrations that ensue at the birth of a girl, the hesitant steps of the child approaching puberty, the circling of vultures over their prey and the auction (the Chira ceremony) by which she is handed over to the highest bidder…

…Born with tiny bells

attached to her fate,…

…The girl will make her name,

will feed her family,

and become a brothel keeper herself.

That was the title

bestowed upon her

while she was in the cradle…

… The news of her being mature

spread like wildfire

in or around a dozen towns.

Then, they all —

the rich and the reputed —

crowded at the spot,

to grab the prize…

… The flesh put on got hung in the abattoir.

She wore the bangles on her hands.

The auction was on …

Another poem tells the tale of a girl named Chhabi:

‘… Even now,

Chhabi attends to her work.

Her mother goes begging

all through the day.

Until her youth lasts,

the business is in full swing.

Once the skin gets wrinkled,

people lose interest in flesh.

Then, hunger gives way to penury…

… Her brother Kisnya

used to entice the clients…

…Since then, people knew him as a pimp.

Once, he stabbed someone;

No one saw him ever since…

… After all, it’s business

that helps a man survive.

The business feeds us.

The clients are our guardians.

And the business is all —

our country, our religion…

…‘Whose daughter is Chhabi?'

Mother doesn’t reply.

Now, Chhabi regards the clients as her parents,

as her kith and kin

and produces the day’s nausea

before God’s abode.

Even now,

Chhabi attends to her work.

Rathod likens poetry to someone who stays close to his bosom and does not let his heart turn to stone. Rathod says that a poem “appears before me in the form of my mother, my lover, and my friend. It stays with me like an inseparable shadow”.

He chides the imagined reader’s supposed reaction to his verse as it lays bare his pain:

… What a wonder

you wish me, ‘Live long.’

You describe sorrow

using the epithet, ‘Beautiful.’

at what age

has it really been beautiful?

… in the life of others,

pain is alright…

…I’m burning

from within

like a cotton bale.

The body is pest-stricken.

The system called cancer

has eaten away all our grace and courage.

This life and this poem

are but its drawings…

Rathod writes with pride about the history of the Lamaan Banjara tribe and their contribution to the nation’s fight for freedom. He cites notable persons from the community: Tapasu and Bhillak, the brothers blessed by Buddha; Lakhkhi Banjara, the trader who lit the funeral pyre of Guru Teg Bahaddur Singh; Govindgeer, a renowned Banjara freedom fighter; Bhai Manasukh, Makhkhan and Maniya, who propagated Sikhism; Phoolan Devi, who refused to submit to caste atrocities and rose to be one of the most feared dacoits. A poem in the collection pays tribute to Umaji Naik, who led a ferocious revolt against the British and who was eventually martyred, yet whose story lies buried and forgotten by history.

Veera Rathod draws explicit inspiration from poets of the Bhakti tradition such as Jnaneshwar, Tukaram, Eknath and Kabir. His words to Tukaram are particularly moving:

…O Tukaram!

Let your abuse

be mingled with my blood. Let my life

be merged with your ovi…

…‘Where has Tukaram, the grocer, gone?

Search him, find him out,

get hold of him,

and drown him.'

These whispering words

are still in the air,

but they won’t trace Tukaram

at any cost.

He’s quite safe

in the hollow of the eyes,

in the hollow of the skull,

in the hollow of the breast,

in each and every vein.

He’s preserved

and will survive

till the life’s last breath…

Veera Rathod’s poetry weaves a tapestry that vividly depicts the life culture, tradition, values, and folklore in the life of the nomadic tribes. While his portrayal also confronts their historical pain, he does not dwell in despair. As the poet writes:

My poems vow that even though our past was crippled, our present and future must be safeguarded. I don’t want to merely portray pain and suffering through my poems; nor...beg…for sympathy or mercy.

Rathod writes in Marathi and Gorboli. Bless Us All, a book published by Red River Press, is the English translation by L S Deshpande of Veera Rathod’s Marathi book of verse, Sen Sai Ves. The translation into English is competent. However, at several places, the Marathi is ‘sanitised’, thereby losing the thrust and rawness of the original Marathi poem.

Nevertheless, it is an enormous task to have conveyed Rathod’s poetry to a much wider audience, thereby also bringing to a wider readership the life, traditions and character of the Banjara community.

Issue 122 (Jul-Aug 2025)

-

MANAGING EDITOR'S NOTE

- GSP Rao: Managing Editor’s Note

-

EDITORIAL

- Gopika Jadeja & Kanji Patel: Editorial

-

ARTICLES

- Hariram Meena: Adivasi Poetry in Hindi

- Lakshmi Priya N: The Rise of Adivasi Poetry in Kerala

- Samarth Singhal: Bhajju Shyam's Creation - Adivasi Art in the Anglophone Picture Book

- Sangeeta Dasgupta and Vikas Kumar: Revisiting the Archive, Reframing the Adivasi - Birsa Munda and Sido Murmu

- T Keditsu: A Poet's Reflection on Poetry in English from North East India

-

INTERVIEW

- Gopika Jadeja: Interview with Poonam Vasam

-

REVIEW

- Anjali Purohit: Bless Us All by Veera Rathod, translated by L S Deshpande

-

ADIVASI POETRY FROM ACROSS INDIA

-

1. SOUTHERN INDIA

- 'Odiyan' Lakshmanan

- Dhanya Vengacheri

- Lijina Kadumeni

- Prakash Chenthalam

- Sukumaran Chaligadha

- Suresh M Mavilan

-

2. WESTERN INDIA

- Babu Sangada

- Bakula Chaudhari

- Bharat Daundkar

- Hariram Meena

- Jitendra Vasava

- Kusumtai Alam

- Manish Meena

- Rekha Kharadi

- Ushakiran Atram

- Vajesingh Pargi

- Veera Rathod

-

3. EASTERN AND NORTH-EASTERN INDIA

- Anil Kumar Boro

- Anju Basumatary

- Anpa Marndi

- Ayinam Ering

- Bikash Roy Debbarma

- Desmond Kharmawphlang

- Emisenla Jamir

- Esther Syiem

- Jiwan Namdung

- Kavita Karmakar

- Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih

- Ponung Ering Angu

- Rajen Kshetri

- Sameer Tanti

- Snehlata Negi

- Streamlet D’khar

- T Keditsu

- Uttara Chakma

- Yumlam Tana

-

4. NORTH AND CENTRAL INDIA

- Alice Barwa

- Anuj Lugun

- Basavi Kiro

- Bhanuprakash Singh Meda

- Chandramohan Kisku

- Hemant Dalapati

- Ishan Marvel

- Naseem Akhtar

- Nirmala Putul

- Parvati Tirkey

- Poonam Vasam

- Satish Loppa

-

1. SOUTHERN INDIA