Maitreyee B Chowdhury

02. Maitreyee B Chowdhury

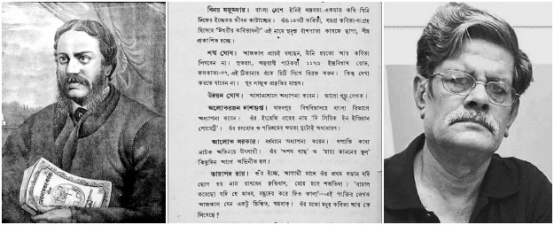

(From left) Michael Madhusudan Dutt, a page from Krittibas 1965 edition, and Malay Roychoudhury.

The need for a change in perspective ushers revolutions

What do people mean when they talk about revolution? There is no doubt that as a historical process, revolution is an important phenomenon, one that is both inevitable and transformative. In literature, a revolutionary act often comes about from society’s need to see things from a different perspective.

One of the earliest acts of revolts in poetry from Bengal, was probably by Michael Madhusudhan Dutta, a poet who took Bengal by storm. His Meghnad Badh Kavya, a poem written in blank verse narrates the story of the death of Ravana’s son Meghnath. Contrary to the popular black-and-white characterisation of Ram and Ravana, Michael Madhusudhan chooses to make the demons in Valmiki’s Ramayana heroes. Megnath is presented as the protagonist, while Ram and Lakshman become antagonists. There’s of course an undeniable hint of Meghnath and Ravan as the defenders of their land against Ram and Lakshman who are presented as the outsiders much like the Britishers.

During the pre-partition days, the united land that was Bengal was home to many prominent names that made their mark on the map of poetry. Before the advent of Rabindranath Tagore on the scene, most of the poetry that was being written was descriptive. To this descriptiveness, Tagore added the act of looking inward. His poetry was a blend of thought, philosophy and spirituality-attributes that were new to the era. In that sense, Tagore’s poetry gave a new dimension to the readers.

Thou hast made me endless, such is thy pleasure. This frail vessel thou

emptiest again and again, and fillest it ever with fresh life.

This little flute of a reed thou hast carried over hills and dales, and hast

breathed through it melodies eternally new.

At the immortal touch of thy hands my little heart loses its limits in joy and

gives birth to utterance ineffable.

Thy infinite gifts come to me only on these very small hands of mine. Ages

pass, and still thou pourest, and still there is room to fill.

(From Gitanjali)

Tagore’s lyricism encapsulates his love for the natural world, arts and music, all of which found a place in his poetry. From a simple description of nature, Tagore takes his readers into a place of deep introspection. This was something that Bengali poetry hadn’t witnessed yet. It was his way of changing the way the world looked and wrote poetry.

In direct contrast to Tagore’s romantic poetry, was the land that was being ravaged by colonial brutality. Unemployment, poverty, and rage were at an all-time high in Bengal. If literature, was a mirror to society, Tagore’s poetry had begun sounding absurd to many. In a sense, this was the beginning of a defiance that startled its onlookers.

As if on cue, in the year 1922, a young poet Nazrul Islam, published the poem ‘Bidrohi’. The poem was not only ahead of its time, it was essentially a cry for revolt. A revolt against appeasement, against cowing down to brutal forces, and a cry for holding one’s head high.

I'm ever uncontrollable, irrepressible.

My cup of elixir is always full.

I'm the sacrificial fire,

I'm Yamadagni, the keeper

of the sacrificial fire.

I'm the sacrifice, I'm the priest,

I'm the fire itself.

I'm creation, I'm destruction,

I'm habitation, I'm the cremation ground.

I'm the end, the end of night.

I'm the son of Indrani,

with the moon in my hand and the sun on my forehead.

In one hand I hold the bamboo flute,

in the other, a trumpet of war.

I'm Shiva's blued-hued throat

from drinking poison from the ocean of pain.

I'm Byomkesh, the Ganges flows freely

through my matted locks.

Bidrohi managed to shake people from complacency. The youth of Bengal took to it like fish to water, it became their war cry. For many, poetry would never remain the same, its purpose was suddenly redefined. Nazrul went on to write many revolutionary songs and poems that are popular to date, and strangely enough, as universal as Tagore’s poems. Nazrul reminded people that poetry could be a vehicle for bringing about social change. He soon joined the wave of modernist poets- a group, that sought to write very different kinds of poetry. Nazrul's poetic temperament was eclectic, and in matters of diction, he often borrowed from various languages like Hindustani (Urdu) or even Arabic to enrich his style.

Nineteenth-century Bengal was a time of chaos and social churn. Like the many social reformers, poets joined the battle for change too. Aided by newspapers, literary magazines and journals, this wave turned into a literary movement of sorts. One magazine that particularly stood out was Kallol. The magazine played a very important role in ushering change in Bengali literature. Established in 1923, it highlighted avant-garde writing, and the work of those who were experimenting with both form and content. The journey of Kallol and its writers, in turn, became the journey of one of the first literary movements in Bengal.

Thanks to these new trends, many amongst the young group of writers began voicing their concerns about the prevalent romantic style of writing. A fierce debate soon ensued between the old guard and the new. Many of the protesting writers were inspired by Marxist and Freudian thoughts. Also, what created a furore was the fact that many of these young writers were not only opposed to the Tagorean kind of writing but also wanted to completely move away from this style. Amongst these new and young voices were names like Kabi Nazrul Islam, Premendra Mitra, Manindra Dey, Bishnu De, Buddhadeb Basu and Jibanananda Das.

The debate between the young writers versus the elderly ones was spearheaded mostly by two magazines. A literary magazine called Shanibarer Chithi was founded as a retort to the younger voices. The younger lot, in turn, was represented through the Kollol magazine. Inadvertently, Tagore himself became a part of this feud, despite being the only one who was respected by both groups. But since the revolt had much to do with the kind of writing that he had made famous, he could hardly be an onlooker. Ironically enough, Kollol even ran an essay by Tagore during this time. In this essay, he defended his idealism, while appreciating the efforts of the younger writers. The essay raised concerns about realistic literature, which according to him felt like a tokenism towards issues related to poverty, while also being unnecessarily provocative about unrestrained lust. However, Tagore came out with gadya kabita (free prosaic verses) around this time, which somewhat halted the debate. However, the Kallol era debate was suddenly brought to a standstill with the death of its editor Gokulchandra. But this conversation had effectively given birth to a new wave of Bengali modernistic writing, which now seemed difficult to underplay.

The modern and post-modernist times have produced several worthy names from Bengal. One name, however, towers above them all as the true successor to Tagore. Poet Jibanananda Das’s poetry stands like an isolated island. It is enchanting, yet terribly alone, introspective and magnificent. While a stream of Bengali poetry flowed by him, none of it could ever breach Jibanananda’s thought process or his sublimity. Like other modernists, Jibanananda wanted to change the way poetry was being written. Though he shared Tagore’s deep affinity with nature, unlike Rabindranath, he portrayed humanity’s frustrations, depression and the loneliness of modern urban life in his poems. In terms of technicalities, many of his poems, sound like prose, a tendency that not only influenced but was also imitated by subsequent poets. Unlike Tagore, Jibanananda’s poetry is neither spiritual nor idealist. He paints with such skill and sensuousness, that his diction carries the reader to a place of vivid imagination.

For aeons have I roamed the roads of the earth

From the seas of Ceylon to the straits of Malaya

I have journeyed, alone, in the enduring night,

And down the dark corridor of time I have walked

Through the mists of Bimbisara, Asoka, and darker Vidarbha.

Round my weary soul the angry waves still roar;

The only peace I knew with Banalata Sen of Natore.

Her hair was dark as the night in Vidisha,

Her face the sculpture of Sravasti.

I saw her, as a sailor after the storm

Rudderless in the sea, spies of a sudden

The grass-green heart of the leafy island.

“Where were you so long?”, she asked, and more

With her bird’s-nest eyes, Banalata Sen of Natore.

As the footfall of dew comes evening;

The raven wipes the smell of the warm sun

From its wings, the world’s noises die,

And in the light of fireflies the manuscript

Prepares to weave the fables of night;

Every bird is home, every river reaches the ocean.

Darkness remains – and it’s time for Banalata Sen.

(From Banalata Sen-Translation by Chidananda Dasgupta)

The Calcutta of the 1940s was a political and social hotbed. The Quit India movement; the horrifying Bengal Famine; the Indian National Army trials; and the communal backlash from partition—all of this deeply affected the poetic gaze. And with World War II affecting everyone’s lives, writers realised that poetry could no longer remain idealistic and untouched. This feeling not only gained traction through the war years but persisted as an aftermath. Added to this, the rise of Marxist beliefs and compelling questions, made a significant impact on the sensitive minds of poets in Bengal.

Incensed by the pain and trauma, the poet’s language and emotions lay bleeding. Poetry became a direct response to the suffering one witnessed on the streets. Besieged by poverty and sickness, moral degradation and restlessness were the new normal. Language outgrew its refinement and became raw and intense. Poets like Samar Sen, Sukanta Bhattacharya and Subhash Mukhopadhyay were strong voices that emerged during this time. Mukhopadhyay especially, grappled intimately with the massive upheavals of that era. His poems were straightforward and heralded a startling new era in Bengali poetry.

My love,

this is not the time to play with flowers;

we are face to face with the threat of destruction.

My eyes are no longer befuddled with the azure wine of dreams;

my skin is baked by the scorching sun

(Translated by Sumanta Banerjee)

But having faced the relentlessness of this turbulent time, one must not forget those young poets, who had the maturity to not sacrifice artistic virtuosity for political messaging. One remembers Sukanta Bhattacharya in this context.

I am a poet of the famine, nightmares torment me each day,

Death stares me in the face endlessly.

My spring day passes in long lines waiting for food,

The shrill siren screams through my sleepless nights.

I thrill at the sight of blood being spilled senselessly,

And I marvel at my two manacled hands.

(Translated by Anjan Basu)

The journey of Bengal’s poetic revolution can hardly travel about without touching upon the role of the Naxalbari uprising, or the Tebhaga peasant revolution that took place around this time. These movements proved to be immensely influential for the young poets. Communist poet Saroj Dutta summed up the violent mood of the radicalised youth when he said, “Forget the past, forget the old poets. It is only the new poets of the revolution who have emerged from the peasant’s struggle, who are the fighting poets”. Literary magazines of the time, Kobita, Samakal, and Krittibas, also added to the fervour.

With the sixties, began one of the most electric periods in Bengal. The socialist revolution swept through this land, even while the dying influence of writers like Buddhadeva Bose, placed others on centre stage. Poets like Sunil Ganguly, Sankha Ghose, Nirendranath Chakraborty, Shakti Chattopadhyay and others, had begun ruling this poetic universe now. Formal trends in poetry seemed to have been banished altogether. The new poets brought in new idioms and expressions, often influenced by Marxist theories, but mostly from their own experiences of life.

Poets writing around this time often initiated new trends as a matter of revolt. Like in the Kollol era, Krittibas magazine (1953) played a major role in defining the journey of these poets. As a result, they came to be known as the Krittibas poets. Sunil Gangopadhyay one of the most prominent names from this group had said once, "The name Krittibas is not just only a name of a magazine, our vibrant youth, our dreams, our arrogance, our desires, sweat, all are integrated with this name.”

The poetic style and diction adopted by these poets were mostly spontaneous. Both the ugly and the beautiful, seemed to inspire them. The quest to be real, shorn of all artificial adornment, also led to experimentation with the use of slang in poetry. While this came as a shock to most readers who were used to genteel language in poetry, the Krittibas poets justified the usage as a requirement for realistic expressions.

But despite the criticism, this era was not without its poetic beauty. Sunil Ganguly’s Neera poems for example, a series on love and lusciousness dedicated to a mysterious woman called Neera proved to be very popular.

I shan’t sleep for a year, wiping the sweat off the brow

At dawn after a dream seems so very foolish

I prefer forgetfulness, as free of shame as

The naked body hidden in clothes, I

Shan’t sleep for a year, for a year I’ll be awake, dreamless

And roam your body, like the fifty-two holy places,

To earn my piety.

(From For Neera, Suddenly. Trans. Arunava Sinha)

Shakti Chattopadhay, another big name from this era, wrote unconventional poems that were best suited to his bohemian spirit. A certain rawness, a lyrical quality, and rebellious charm added to Shakti’s wild popularity. As someone who had seen extreme poverty, Shakti’s poetry broke away from most rules governing society. Rebellion enveloped every inch of his poems. In that sense, he was the most profound lover and the biggest revolutionary of them all.

I think it best to turn around…

I think it best to turn around

My hands smeared so black

For so long

Never thought of you, as yours

When I stand by the ravine at night

The moon calls to me, come

When I stand by the Ganga, asleep

The pyre calls to me, come

I could go

I could go either way

But why should I?

I shall kiss my child’s face

I’ll go

But not just yet

Not alone, unseasonably

(Translated by Arunava Sinha)

On the heels of the Krittibas poets, came a band of young poets born of the same cultural milieu, the same angst, and the unapologetic attitude in their disruptiveness. They aimed at breaking the shackles of society by taking matters into their own hands. Known to the world as the Hungry Generation poets, this group hit the Bengali literary world with a force that shook an entire generation. Established by brothers Malay and Samir Roychoudhury, along with Shakti Chattopadhay and Debi Roy (aka Haradhon Dhara), the primary aim of this movement was to confront and disturb preconceived literary canons.

The Hungry Generation Movement started in Calcutta during the early 1960s and managed to influence other writers from various parts of the country. Hungryalist poet Shaileshwar Ghose, describes this trend, “I say what I feel. I feel frustration, hunger for love, hunger for food.” The group employed radical methods to attract attention. Though wildly popular with the youth, they were severely criticised by other poets and writers.

In the year 1963, Malay Roychoudhury published a poem called ‘Prachanda Baidyutik Chhutar’ (Stark Electric Jesus). The poem was declared obscene by the authorities, a case was registered against Malay, and he was taken into custody. Raids were conducted against the rest of the group. ‘Prachanda Baidyutik Chhutar’, is a perfect example of confessional poetry, with sexual connotations and rough language. This kind of poetry attempted to transform desire itself into poetry. The poem also defied traditional forms of writing, moving away from the usually used Bengali meters - matrabritto and aksharbritto.

Oh I’ll die I’ll die I’ll die

My skin is in blazing furore

I do not know what I’ll do where I’ll go oh I am sick

I’ll kick all the Arts in the back and go away Shubha

Shubha let me go and live in your cloaked melon

In the unfastened shadow of dark destroyed saffron curtain

The last anchor left me after I got the other anchors lifted

I can’t resist anymore, million glass panes are breaking in my cortex

I know, Shubha, spread out your matrix, give me peace

Each vein is carrying a stream of tears up to the heart

Brain’s contagious flints are decomposing out of eternal sickness

Mother why didn’t you give me birth in the form of a skeleton

I’d have gone two billion light years and kissed God’s ass

But nothing pleases me nothing sounds well

I feel nauseated with more than a single kiss

I’ve forgotten women during copulation and returned to Muse

Into the sun-colored bladder

I do not know what these happenings are but they are occurring within me

(“Stark Electric Jesus,” as published in City Lights Journal)

The modernist avant-garde tendencies in Bengali poetry often walk a tightrope in trying to find the sweet spot between love and language. In the years that followed the Hungryalists, contemporary poets like Binoy Majumdar or Joy Goswami delved into poetry that while being personal, also harboured universalization.

And because the love of poetry defines most Bengalis, this journey of revolt, churn and introspection is not only interesting but often seems personal to most who have travelled and been witness to this spectacular path.

Issue 114 (Mar-Apr 2024)

-

EDITORIAL

- Angshuman Kar: Editorial Comment

-

ARTICLES

- 01. Angshuman Kar: Post-Independence Bengali Poetry of West Bengal and Railway Tracks

- 02. Maitreyee B Chowdhury: Revolution in Bengali Poetry

- 03. Parthajit Chanda: Bengali Poetry of the 1950s - A Mysterious Archipelago

- 04. Himalaya Jana: Fallen Butterflies, Resurrected Words - The Poetry of the Sixties

- 05. Chirantan Sarkar: Poems of Defiance of the 1970s

- 06. Hindol Bhattacharya: Between the Idea and the Reality: Situating the Poetry of the 1980s

- 07. Mandakranta Sen: Bengali Poetry – The Last Decade of the Last Century

- 08. Subhadeep Ray: Shunya as a Beginning - Journeys and Ruptures in Bengali Poetry of the First Decade of the Twenty-first Centuryi

- 09. Ashish Gangopadhyay: Reshaping of Bengali Poetry in the Second Decade of the Twenty-first Century: Emerging Trends and New Directions