Sapna Dogra

Sapna Dogra

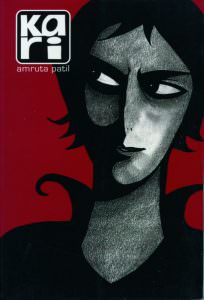

(Image Credit: Book Cover Kari)

Abstract

The very first Indian graphic novel in English by a woman, Kari (2008) by Amruta Patil brings forth a queer protagonist and deeply engages in the ‘ways of seeing’. This article seeks to address the following questions: in what ways is this graphic novel a representational text of queer gaze? What are the modes of resistance for the dominant gaze vis a vis city and its inhabitants? How queer gaze dismantles the binary notions of being and telling that dominant heterosexual storytelling deploys. The resultant decentring, that Patil seeks to foreground, and relocate the aspect of desire, love and friendship.

Keywords: Amruta Patil, Kari, queer, graphic novel, ways of seeing, queer gaze.

Ways of Seeing: Queer Gaze

Feminist film theory emerged post John Berger’s landmark book, in 1972 in which he looked at how women are objectified in the arts. Berger put forward the observation that as far as visual culture is concerned, from oil paintings of European tradition to advertising, men look and women are looked at. In 1975, the term ‘male gaze’ was coined by the film critic Laura Mulvey in her well-known essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. She argued that the cinematic portrayal of women aims at the objectification of women on the screen which robs them of agency. Mulvey’s essay was the foundational text that explored the notion of gaze and depicted women from a heterosexual perspective with women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer. It is only recently that the notion of gaze has been appropriated in queer studies. Caroline Evans and Lorraine Gamman (1995) challenged the gaze theory by underlying the heteronormative assumptions behind them that leave no place for the queer gaze (Tobin 2010). Queer gaze has increasingly come to be understood as a phenomenon of how queer people study and create art, a “gaze that unsettles power relations, creating space for queer transformations and a new way of existing in the world” (Moss, n.p.).

If “male gaze” as defined in Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, objectifies women as stereotypes for heterosexual male viewers, and the “female gaze” responds to this by subverting the object and positioning women as viewers, then both stem from social power buried with the act of looking—who sees and who is seen. In theory, a queer gaze would deconstruct such gender-based power dynamics, changing not only the object but also the intent of the male and female gaze. Ideally, a queer gaze would create a world completely free from binary notions of desire and storytelling, creating space for plural identities and possibilities (Moss, n.p.).

It is this notion of creating a space for plurality that we see in the opening panel of Kari. We see two women, Ruth and Kari, moments before they commit suicide. Kari is a lesbian who is in deep love with another woman, Ruth. The panel is a tribute to Mexican painter Frida Kahlo’s exquisite painting The Two Fridas (Las Dos Fridas), which she painted in 1939 after her separation from her long-time partner Diego Rivera. It depicts two versions or sides of Frida: one rejected by Diego and the other embraced by him. In the painting, Frida’s heart is bleeding. It can be argued that Kari and Ruth may be the same person - or versions of each other. Later we see Ruth and Kari both jump from their respective buildings simultaneously. Whereas Ruth lands in a safety net below her building and is seen on a flight to a distant land beginning a new life, Kari lands in a sewer from where she comes out unhurt but emotionally wrecked. What follows in the course of the novel is how Kari, still reeling from her separation from Ruth, navigates the city of Mumbai.

Queer and the City

Kari is set in the city of Mumbai. “Patil’s Kari is an important revelation of how the city which is supposed to be progressive and modern still continues to harbour a highly heterosexual understanding of society. She uses the metaphor of suffocation in the “smog city” (Patil 13). This metaphor seems emblematic of the unrest Kari experiences and perhaps alludes to the suffocating nature of the heteronormativity in this metropolitan city” (Mahurkar n.p.).

The novel then begins to emerge as a narrative of a young woman finding herself in Mumbai city which is often compared to a sewer. Kari has a nuanced depiction of the grimy physical aspect of the Mumbai city sketched in black and white. We see the dirt, feel the smell and visually indulge in the not-so-attractive parts of the city. When asked about what inspired her first graphic novel, Kari, Amruta says,

Well, I write and draw. So combining the two things was the most obvious thing to do. That explains the choice of form. Kari is about a young woman who is on the brink (literally teetering on the ledge of a building) two times over in the book. The first time around, she chooses to jump. The second time around, she chooses not to. The book is about that journey. I wanted to send out an unusual protagonist into the Indian literary scene. A young, deeply introverted, asocial and queer woman - a counterpoint to the hyperfeminine prototypes one keeps coming across. And yet, the book is not a coming-out tale. Kari’s queerness is incidental, rather than central to her journey. She is dark and funny and detached - something you may not expect from a quickie ‘suicidal lesbian’ synopsis. People love quick synopses. . .

I was keen to try a crossover literary form—it is more texty than most comics or graphic novels—and the story flows from voice-over style narrative text to visuals, and then back to voice-over. As I say in every interview—various experiments are going on in Kari—some are not particularly successful, others have worked out ok. The book is very raw—I was working on instinct. Future work will have resolved these experiments in a better fashion (Patil as quoted in Gravett, n.p.).

Kari describes Mumbai city in terms of its smells while travelling in a train. The city for Kari is not a place of liberation but a space of alienation and angst that one finds in the modernist poetry of T. S. Eliot. Kari’s squalid living quarters presented to the readers through a sketch of the floor plan is a vivid depiction of her cramped existence, physically as well as emotionally.

I try to breathe as little as I can to prevent smog city from choking me. I wish I could detach my lungs. Every day, the city seems to be getting heavier, and her varicose veins fight to break out of her skin. Soon we must mutate—thick skin and resilient lungs – to survive this new reality (Patil 13).

As a writer in an ad agency, Kari juggles between the personal and the professional. As the story unfolds, we see her navigating the roads of the city that are unending like her thought process.

Dismantling Binary Notion: Being and Telling

A queer gaze, like that of Kari, clearly shifts away from Mulvey’s idea of looking and rather becomes a way of being. In being queer the line between the active male and passive subject female dissolves to create a fluid gaze. As a queer woman, Kari journeys across the smog city of Mumbai, engaging in conversations that border on heteronormativity, she experiences visions of Ruth, is rebellious in the acceptance of the societal expectations imposed on her and is deeply sensitive to how things exist on a physical as well as a metaphorical plane.

I play with fruit that the girls and I are too broke to buy. Avocado, kiwi, mangosteen. There are some fruits you do not want to venture into alone. A peach, for one, creature of texture and smell, sings like a siren. A fruit that lingers on your fingertips with unfruitlike insistence, fuzzy like the down on a pretty jaw. Figs are dark creatures too, skins purple as loving bruises. A fig is one hundred per cent debauched. Lush as a smashed mouth. There, I said it again: Lush (Patil 66).

Once while looking at a snow globe, she muses to herself, “What is it about snow globes” she asks at one point, “that makes them fascinating and terrifying at once?” In an interview with Paul Gravett, Amruta Patil says,

I wanted to send out an unusual protagonist into the Indian literary scene. A young, deeply introverted, asocial and queer woman - counterpoint to the hyperfeminine prototypes one keeps coming across. And yet, the book is not a coming-out tale. Kari’s queerness is incidental, rather than central to her journey. She is dark and funny and detached - something you may not expect from a quickie ‘suicidal lesbian’ synopsis. People love quick synopses (Patil as quoted in Gravett, n.p.).

Even at the level of telling we see that Amruta deviates from simple caricatures to a variety of drawing and illustrating techniques that add gravity to her words. There is an eclectic use of pencil sketches, pens, solid markers, crayons, etc. The novel is like a personal diary of Kari, strewn with snapshots of the city as captured by her photographic mind. Kari, the woman with “burning eyes” (Patil 71), mostly comes across as a no-nonsense character with a deep and sensitive understanding of society and gender.

Decentring and Relocating

In Kari, the queer gaze becomes a force of liberation that decentres and relocates power relations. Kari’s struggle, from the very beginning, to locate her homosexuality and recent breakup is heartbreaking. The plot moves back and forth in time with Kari finding herself in unique situations where she struggles to locate the centre of her identity and being. Every time she’s questioned about Ruth, her roommates, boyfriend, she grapples to define her own space. Her bond with Ruth colours her life, symbolised by the coloured panels showing Kari and Ruth in an otherwise black-and-white book. Her persistence to survive is heartening,

The day I hauled myself out of the sewer – the day of the double suicide – I promised the water I’d return her favour. That I’d unclog her sewers when she couldn’t breathe. I earned me a boat that night (Patil 31)

Kari’s friendship with Ruth, Lazarus and Angel is one of the central themes of the novels. One cannot miss the religious undertones in the names of Ruth, Lazarus and Angel. All the characters are instrumental in making Kari attain a spiritual awakening in the face of life and death. In Lazarus, she finds someone who lets her be who she is,

Laz and I have been walking around the city at night, camera in hand, watching homeless people deep in slumber. They sleep on roadsides, under carts and benches, on platforms. Arms holding bodies, legs under legs, a defensive ball against the threats that whiz past at night. It is an appalling thing, this watching. If our subjects were wealthier, we’d be arrested for being peeping toms. As it is, our walk makes for arty b&w pictures of grim urban life (Patil 78)

Kari is an introspective and opinionated woman who speaks her heart out to the readers. Her revulsion with any comment on her physical appearance that ought to manifest femininity is seen towards the end when she chooses to ignore the comment of the barber who reluctantly gives her a boy’s haircut and her reaction to people telling her to be feminine.

‘Madam, won’t looking good. I have Lady’s patterns. … Madam, face looking boy type.’ (Patil 107)

“It’s not that I have a bad relationship with the mirror. On the contrary, I think mirrors are splendid, shiny things that make great collectables, whether whole or in smashed bits. Problem is, I just don’t know what they are trying to tell me. These things can be troubling. The girls are outside the door, telling me to wear kohl, and here I am wondering why I ain’t looking like Sean Penn today.” (Patil 60)

All in all, Kari's attempt at healing herself and accepting herself and the people around her makes Kari a coming-of-age graphic novel that decentres and relocates things that are generally accepted as a norm.

Conclusion

Through Kari’s rebellion against hetero-normativity and the constricted notion of femininity, we are offered a unique protagonist that brings alive the queer gaze. Kari’s constant search for her identity as a woman and a deep struggle to understand society is beautifully portrayed in her relationship with Ruth, Lazarus and Angel. The queer gaze dismantles the binary notions of being and telling that dominant heterosexual storytelling deploys. The resultant decentring, that Patil seeks to foreground, and relocate the aspect of desire, love and friendship.

Works Cited

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. Great Britain: Penguin Books, 1972.

Datta, Surangama. “Can You See Her the Way I Do?’: (Feminist) Ways of Seeing in Amruta Patil’s Kari (2008).” Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, vol.4 no.1, 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.20897/femenc/7917. Accessed 10 September 2023.

Evans, Caroline, and Lorraine Gamman. 1995. “The Gaze Revisited, Or Reviewing Queer Viewing.” A Queer Romance: Lesbians, Gay Men and Popular Culture. Ed. Paul Burston and Colin Richardson. Routledge, pp.13-56.

Gravett, Paul. (2012). “Amruta Patil: India’s First Female Graphic Novelist.” Paul Gravett: Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga. 4 September 2012, www.paulgravett.com/articles/article/amruta_patil. Accessed 10 September 2023.

Mahurkar, Vaishnavi. “Kari: A Graphic Novel About Lesbianism and Big-City Love.” feminisminindia.com, 28 March 2017, www.feminisminindia.com/2017/03/28/kari-book-review/. Accessed 10 September 2023.

Moss, Molly. “Thoughts on a Queer Gaze.” 3ammagazine.com, 2019, www.3ammagazine.com/3am/thoughts-on-a-queer-gaze/. Accessed 10 September 2023.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”.

https://www.asu.edu/courses/fms504/total-readings/mulvey-visualpleasure.pdf. Accessed 10 September 2023.

Patil, Amruta. Kari. New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2008.

Tobin, Erin Christine. Towards a Queer Gaze: Cinematic Representations of Queer Female Sexuality in Experimental/Avant-Garde and Narrative Film. 2010. University of Florida, MA Thesis. ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0041416/00001. Accessed 10 September 2023.

Issue 110 (Jul-Aug 2023)

-

EDITORIAL

- Sapna Dogra: Editorial Comment

-

ARTICLES

- Meghna Borate-Mane: Decoding Human-Animal Hybridity in Trauma Graphic Narratives

- Rani Alisha Rai: The Fluidity of Graphic Novels Through a Study of Sarnath Bannerjee’s Corridor

- Rituparna Sengupta: Goddess or Woman, Pativrata or Feminist? - Sita in Two Contemporary Graphic Narratives

- Sakshi Wason: Which ‘Side’? Displacement and Dispossession in Sa’adat Hasan Manto’s “Toba Tek Singh” and Vishwajyoti Ghosh’s This Side That Side: Restorying Partition

- Santanu Saha: Indian Women Fighting Back in Kuriyan and Das - A Comparison in Retrospect

- Sapna Dogra: Dismantling Binary Notion of Being and Telling - Queer Gaze in Kari

- Shweta Mishra: The Indian Graphic Novel - A Distinct ‘Comic’ And ‘Serious’ Text-Image Medium

- Sreya Mukherjee: City as Text, City as Palimpsest - A Critical Reading of the Urban Spaces in the Graphic Novels of Sarnath Banerjee

- Sreyasi Mitra:Nature‘s Voices - Ecofeminist and Ecocritical Perspectives in Indian Graphic Narratives

-

CONVERSATIONS

- Sneha Rita Sebastian and Resham Anand: Graphic Narratives in the Digital Age - In Conversation with Bhaghya Babu

- Sonal Dugar and Ila Manish: Drawing from the Real World - Ita Mehrotra on Storytelling from Beyond the Studio