Rituparna Sengupta

Rituparna Sengupta

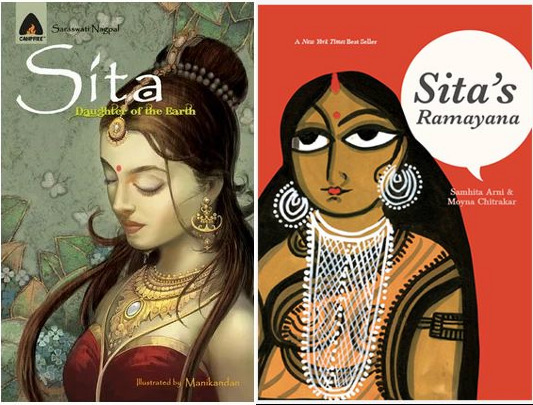

(Cover images of Sita: Daughter of the Earth by Campfire and Sita’s Ramayana by Tara Books)

Abstract

This article is an analysis of the representation of the mythological character of Sita in two contemporary graphic narratives, Sita: Daughter of the Earth (Nagpal and Manikandan) and Sita’s Ramayana (Arni and Chitrakar). It studies these two texts for their negotiations of womanhood and goddess-hood, patriarchy and feminism, through their varying interpretations of Sita’s subjecthood, agency, and resistance. It demonstrates how Sita, as ‘a daughter of the earth’, is variously an obedient subject to the Law of Patriarchy (the pativrata nari) and a questioning subject who challenges patriarchy’s foundational values and discovers strength in solidarity with victims of patriarchal violence. How does Sita come of age in the course of these narratives? How can the same epic tale, narrated from a woman’s perspective, be presented as a celebration of self-fulfilment in one adaptation, and a lament of tragic self-effacement in another? How does the relationship between word and image in these graphic narratives serve to add layers to the story and lay bare its ironies and contradictions? Through an examination of key incidents from these narratives, such as the pivotal agnipariksha episode, this article argues that contradictory interpretations of Sita’s symbolic significance continue to flourish in contemporary (graphic) adaptations of her story.

Keywords: Sita, Mythology, Graphic Narrative, Pativrata, Feminism

The mythological figure of Sita from the Ramayana endures in popular and sacred narrative traditions in a range of adaptations. Traversing different, even contradictory ideological positions, she serves diverse symbolic functions across varied negotiations of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’ pertaining to Indian womanhood. In this article, I will analyse two representations of Sita in two very different graphic narratives—the Campfire title Sita: Daughter of the Earth and the Tara Books title Sita’s Ramayana. My emphasis will be on these texts’ negotiations of feminism and patriarchy through their varying interpretations of Sita’s subjecthood, agency, and resistance. How do these texts aiming for a modern adaptation of an assertive, even feminist, Sita, reconcile readings of her as a pativrata woman, devoted to her husband? How do they portray climactic episodes like Sita’s agnipariksha (trial by fire) and her eventual subsumption into the earth, which have given rise to a vigorous debate about whether Sita is a victim of patriarchy or a rebel against it? Does a narrative that presents itself as emerging from a woman’s point of view necessarily carry a female gaze? How do word and image work together in these graphic narratives to add layers to the story or reveal its ironies and contradictions?

Sita: Daughter of the Earth —‘ Pativratisation ’ as Agency

Sita: Daughter of the Earth is one of the three ‘mythology’ titles on the Ramayana by Campfire, a publisher of graphic novels for children and young adults. The book is a retrospective first-person narrative by Sita, moving between an omniscient point-of-view (as a goddess) and an intimate, personal account (as a woman). The cover of the book features Sita as a fair-skinned, demure, and delicate-featured woman with a downcast gaze, dressed in royal finery. The first and last pages of the graphic narrative with their identical framing of Sita, seated on a pile of rocks against the background of a distant city or a cavern, with a halo around her head and a benign expression on her face, visually establish her as a goddess (Nagpal and Manikandan 5, 91). This visual framing is instrumental in the narrative framing of the succeeding events of her life with its many trials and sufferings. Essentially, the graphic narrative functions as a bildungsroman, with Sita narrating the story of her miraculous birth into the royal family of Videha, her coming of age, her marriage to Ram and entry into Ayodhya, her years of exile, abduction, rescue, and eventually, her death. Throughout the text, there is a tension between her status as a goddess and her status as a woman, with her exceptionality repeatedly being contained by the text, as she is shown upholding the values of bourgeois womanhood. Her portrayal as a goddess also serves to present her as somewhat detached from the fate of an ordinary mortal woman, and thus immune to the tragedies of abandonment and self-effacement that are embedded in her tale.

As a child and then as a young woman, Sita is conditioned for her subsequent role as wife and queen. Much of this training is imparted by other women. The silent presence of her mother Bhudevi, the goddess of the earth, across crucial moments in the text, not only serves as a constant reminder of Sita’s divine origins but also gestures towards the maternal surveillance under which she performs her role within patriarchy. This is mirrored in her interactions with her human mother, such as the instance where the epic device of women’s samvada (dialogue) on naridharma (wifely duty) is used to show Sita’s mother advising her daughters departing for their marital home—“in Ayodhya, its king, its people, and its laws are your priorities. Your duty towards them is more important than your own life” (Nagpal and Manikandan 25). Sita receives this as “rare wisdom and insight that only a woman can give” (25). This training in “pativratisation” demonstrates how patriarchy elicits the consent of women in their own “protected subordination” by making female characters celebrate their own subjugation in dialogue with other women (see Shah 80). In fact, even though Sita is depicted as demonstrating an intellectual bent of mind, the textual emphasis is on her fascination with literary accounts of famous Pativrata women of mythology—Uma, Savitri, and Anasuya, with a perfunctory acknowledgement of the scholar Gargi at her father’s court (Nagpal and Manikandan 11-12). Great care is taken by the text to negate her physical exceptionality—such as being able to inexplicably wield Shiva’s immovable bow as a child—through visual and literary emphases on her physical frailty and lack of physical courage. She eventually accepts that she is as “delicate as a flower” and not suitable for the battlefield (14, 44).

This containment is offset by the several ways in which the text constantly manoeuvres to ascribe agency to Sita—even in instances without textual precedence—in its anxiety to assure us of her control over the narrative of her life. This agency is framed in terms of the expression of personal desire, an assertion of equality, and the fulfilment of queenly duty, all of which ingeniously disguise her subjection to patriarchy by presenting it as a matter of her individual ‘choice’. For example, after returning from Lanka, she sends a spy into the Ayodhyan public, learns of her subjects’ suspicion of her chastity, feels intense guilt, imposes self-exile, leaves the kingdom, and forbids anyone from tracing her, absorbing all guilt and effectively removing herself from the Ayodhyan conscience. The verbal and visual reinforcements of a loving and respectful Rama and later a tearful, paining, grieving Ram (Nagpal and Manikandan 27, 72, 74, 80), serve to establish him as a tragic, romantic hero; in fact, Rama and Sita appear as “star-crossed lovers… destined…for a tragic separation” (McLain 93). Importantly, here it is Ram’s status as a man and king rather than as an avatar of a god that is emphasised. This is most explicit in the pivotal agnipariksha episode, where the coldness of Rama’s formal rejection of Sita is undercut by his visual depiction: unable to face her and wearing a pained expression on his face, Rama appears as the tortured husband weeping silent tears for his wife, rather than as the duty-bound king punishing his wife for compromising his reputation, thereby being absolved of any complicity in her suffering. In contrast, Sita’s angry decision to go through the trial by fire and kill herself is presented, like earlier Amar Chitra Katha representations of Sati, not as an “act of self-erasure but an act of self-fulfilment”, rendering irrelevant any questions of external imposition (Chandra, Classic 159).

In fact, each fresh trial in Sita’s life is importantly attributed not to Rama’s cruelty, but to the appeasement of public demand and obedience to an unspecified ‘law’ (of patriarchy). Thus, there are references to “slander spread by the citizens of Ayodhya”, their fickle public memory, and an uncompromising “law of Ayodhya”, which render Sita and Rama helpless (Nagpal and Manikandan 80, 88, 74). At the same time, during the agnipariksha episode, we are told that “aghast” spectators silently watched the spectacle of her fire ordeal without intervention, since it was “after all, a matter only for a husband and wife to settle” (73). This uneasy paradox of Sita’s precarious location as wife and queen, poised between the public and the private realms of social conduct for women, her ‘virtue’ forever under question and in need of divine validation, is reflective of the condition of womanhood at large under the law of patriarchy. This law is as overarching as it is diffuse, attributed to no individual authority, and ostensibly equally applicable to men and women. Thus, Sita’s final trial, when she finally appeals to Bhudevi to extract her from the mortal domain, is presented as a sacrifice she undertakes to protect herself and Rama from further public scrutiny. She addresses Rama thus: “I would love nothing more than to swear thus, and be reunited with you… but mortal memories are fickle. People forgot the agnipariksha in Lanka. And in a few years, people will forget my oath today, and again accuse you and me of violating the law” (88; emphasis mine). She calls upon Bhudevi to take her back to her true origins, as ultimate proof of her chastity. This is the moment she has been preparing for all her life when she is able to live up to her promise to her mother to value Ayodhya’s needs over her own life.

As Sita calls upon her mother Bhudevi to take her away as the final testament to her chastity, once again she presents it as an assertion of her agency: “I finally followed my heart, and thus, made the choice I did” (Nagpal and Manikandan 90). Her abrupt exit thus becomes an act of wish fulfilment and the logical culmination of her lifelong training as a woman and queen. Having thus served her purpose in the text, Sita transforms into a goddess on its last page. She reassures the reader of her irreplaceability in Rama’s life and her lasting legacy as a mother of worthy heirs to a glorious heritage; as Ayodhya’s queen, she is content to surviving vicariously through people’s memories (91). Nevertheless, her last declaration that it is only in the netherworld that she has finally found her “true home” where she “will immortally remain, a daughter of the earth” (91), strikes a discordant note as it leaves an impression of her incongruous existence as a human woman and wife. The combined effect of all these defining events of Sita’s life episodes and her response to them is to suggest Sita’s fully developed awareness and agency in all the defining events of her life, including those of her subjection to perpetual patriarchal suspicion, surveillance, and abandonment. The text’s emphasis on Sita’s goddess-hood consistently thwarts the reader’s identification with her as a mortal woman facing an earthly woman’s ordeals, instead removing her to a distance from which she can only be surveyed as fulfilling a divine, pre-ordained fate, before leaving the earthly realm for the celestial one.

Sita’s Ramayana —Female Fortitude and Solidarity

Sita’s Ramayana is a joint effort by Patua folk artist Moyna Chitrakar and urban writer Samhita Arni. Patua is a multimedia storytelling tradition from rural Bengal, wherein itinerant artists and performers unroll sequential, painted scrolls to accompany their songs that often draw upon episodes from mythology; today the painted scroll can be found detached from its performative context and has made its way into paintings and book illustrations in urban markets (see Chatterji 63-92). Sita’s Ramayana was the product of a workshop training Patua artists to stylistically adapt their scroll art into a graphic narrative, with a view to “connecting Indian picture storytelling traditions with a contemporary reader’s sensibility” (Arni and Chitrakar 152). Although Moyna Chitrakar was formally unacquainted with sixteenth-century Bengali poetess Chandrabati’s anti-canonical Ramayana, and instead drew upon the oral songs passed on generationally by women in her village, it is clear that both renditions belong to the folk narrative tradition where women express their alienation from the masculine, heroic ideals of the epic world, and lament the limited agency of female characters that condemn them to a fate of being “abducted or rescued, or pawned, or molested, or humiliated in some way or the other” (Dev Sen 18). Samhita Arni, following the artist’s paintings and cues, supplied the words for the text, building on the “feminist possibilities of Chandrabati’s Ramayana” (151). When such a narrative is “materially, performatively, and spatially re-oriented, from scroll to book form; from Bengali to English; and from village performance audiences to solitary urban readers” (Krishnamurti 6), several elisions or expansions of meanings can occur in the process.

The cover of Sita’s Ramayana stands in contrast to the Campfire title. Here, Sita is a dark-skinned married woman, dressed as a simple villager albeit decked with jewellery, with her gaze fixed upon the distance and her face reflecting quiet dignity. The narrative begins in medias res, with a slumbering Dandaka forest being animated into consciousness by the presence of a pregnant, abandoned, bruised, and tearful Sita. In contrast to the epic mode of narration that commences by establishing the lineage and pedigree of kings, the narrative here begins with the story of the abandonment of a vulnerable woman, “which positions readers to read the story as the testimony of a woman who has been wronged” (Madan 323). The forest’s wonderment at Sita and its compassion for her are visually portrayed in the form of flowers gathering around her protectively and weeping in solidarity—these are not instances merely of personification or pathetic fallacy, for Forest and Woman here are born of the same womb of mother earth. The forest here is more than a setting; it is the ‘awakened’ forest’s gaze through which we first discover Sita, it is in response to their query that she proceeds to narrate her tale of woe, it is the wind and birds and trees who carry her tale forward, and it is with the permission of the creatures of the forest that she makes her home safely there, banished from “the world of men” (Arni and Chitrakar 9). In her study of four mythological/literary female characters from pre-modern texts across cultures, Catherine Diamond draws attention to how the forest becomes for such women “a site of negotiation between their roles as wives/lovers—their identities in a masculinised world—and their mythical origins in the earth as daughters of chthonic female deities”, a place where “they struggle to create spaces for themselves as individuals” (79). So it is with Sita, who is presented as an observer, commentator, and critic—a different kind of chronicler.

Sita’s story begins with her years of exile with Rama and Lakshmana. Her journey of growth begins with her discomfort at her husband’s proclivity for violence in the peaceful forest, sharpens with her disturbance at his inciting Lakshmana to be violent with Surpanakha, intensifies with her escalating guilt at the chain of violent events that unfold in the name of her rescue, and culminates in her final realisation that she too is trapped within a cycle of violence, at the mercy of men. In the process, she also experiences an increasing sense of identification and solidarity with ‘other’ women, which contradicts the Ramayana’s usual polarisation of women into “good women” and “ogresses” (see Doniger, ch 9). The first visual foreshadowing of this occurs in the episode of Surpanakha’s mutilation, where Surpanakha is not depicted in the usual racially distinct terms of Amar Chitra Katha aesthetics, but in the same visual register as Sita, only with a grey skin tone to mark her difference from Sita’s earthy brown (Arni and Chitrakar 16-17). Importantly, we see Surpanakha’s pain through Sita’s empathetic gaze, as a literally hair-raising spectacle; the same style is used a few pages later, to portray the abduction of a traumatised Sita herself (27). This visual resonance between the two incidents is significant for emphasising the similarity, rather than the distinction, between the predicaments of the two women as victims of male violence. Throughout the narrative, Sita’s latent guilt and secret solidarity—especially with widows and orphans—keep building: with Tara’s widowhood, Hanuman’s incineration of Lanka, and eventually Rama’s long-drawn-out siege of Lanka. In an intriguing plot innovation, Hanuman visits Mandodari in the guise of an ascetic and tricks her in a way similar to Ravana’s deception of Sita—thus, both women from warring kingdoms become the unwitting conduit of male violence.

For a crucial portion of the text, it is Vibhishana’s daughter Trijatha—Sita’s unwilling jailer and true confidante—who is presented as the moral centre of the narrative, positioned uniquely as she is, as both prophetess and an eyewitness narrator to the Lankan war. She laments, “[w]hat is this war, pitting brother against brother? Which kills sons while fathers live? There is no honour in this fighting, no heroes—only deceit and death” (Arni and Chitrakar 91). Sita feels her anguish, yet she still believes in the righteousness of her cause and Rama’s honour, and justifies the inevitability of this tragic outcome by reminding herself that this was all a result of “one man’s unlawful desire” (113); it is only when she faces Rama’s cold cruelty after his triumph in Lanka when he tells her that he had fought the war not for her but to redeem his honour, that she reaches a similar conclusion about him—that Rama’s “honour had exacted a bloody price” (117). Torn between one man’s desire and another’s honour, Sita is disillusioned and finds herself sharing the plight of the Lankan women who became casualties in the war between men. She concludes, “[w]ar, in some ways, is merciful to men. It makes them heroes if they are victors. If they are the vanquished—they do not live to see their homes taken, their wives widowed. But if you are a woman—you must live through defeat…you become the mother of dead sons, a widow, or an orphan; or worse, a prisoner” (120).

Patua’s visual motif of the pointing finger is used with particular effectiveness in Sita’s Ramayana. In the agni pariksha episode, Rama’s accusatory finger raised at Sita accompanied by his explicit words of rejection paints a very different picture from the Campfire depiction of a tortured Rama putting his duties as a king before his feelings as a husband (Arni and Chitrakar 116; see Krishnamurti 11). In contrast to the Campfire tile, here Sita directly confronts Rama with her righteous anger but a silent Rama has no answers for her. At this, Sita is filled with despair and grief at the futility of her pining for Rama and the violence that had ensued from it, and she calls for Lakshmana to build her a pyre. Significantly, the image here of a tearful Sita bent over with bewildered sorrow is strikingly reminiscent of an earlier image of her, crouching in the Ashoka Vatika, waiting for Rama to come to rescue her (Arni and Chitrakar 119, 32). This visual echoing serves to highlight the irony of the situation and draws our attention to the fact that whether in abduction or rescue, Sita’s fate remains one of perpetual desertion. Betrayed and abandoned rather than freed, Sita recalls all the emotional violence she has suffered and is profoundly disillusioned with Rama’s suspicion and mistrust, she wonders if he had ever known her at all, and prepares to enter the fire.

Once her chastity is attested by Agni and she emerges from her trial unscathed, she believes her exile to have ended, like Rama’s, but soon after, when Rama instructs Lakshmana to abandon her in pregnant condition in the forest, she discovers the difference between men’s dignified exile and women’s shameful abandonment (see Dev Sen 26). Here, Sita’s transformation from “Sita, the queen” into “Sita, the simple forest woman” (Arni and Chitrakar 135) is juxtaposed with Rama’s momentary doubt about his duties as a husband and father, before his prompt resumption of his royal responsibilities (136-137). Later, Rama disrupts the peaceful life she has built with her sons at Valmiki’s hermitage and appeals to her to return, although as a queen and mother rather than as a wife. Sita is first angry and then declaring that she does “not care to be doubted again” (145), she hands over her sons to Rama’s care and is taken back into her mother, the earth’s womb. The last image of her, with hands folded in supplication but now tearful, is again visually reminiscent of her agnipariksha and in both instances, it is Agni who appears before her in response to her prayer. The text’s last words that “[s]he disappeared and was never seen again” (148-149), accompanied by her sobbing farewell, stands in contrast to Campfire Sita’s content acceptance of the same fate and her happy release from the mortal world. If in Campfire, she sits enthroned as a goddess in the depths of the earth, her “true home” (Nagpal and Manikandan 91), then here, she seems to be engulfed by the earth, vanishing into the darkness, frozen in one last act of praying for disappearance.

Whether or not Sita’s Ramayana is a feminist text, is open to interpretation, depending on what we expect from a feminist narrative. Sita may not be able to thwart her tragic fate or avenge her suffering within the diegetic limits of the Ramayana narrative. At the same time, Sita is also not a vehicle through which patriarchy successfully indoctrinates women into bearing injustices and suffering silently, instead, she learns to transcend her personal grief by growing into a realisation of shared sisterhood. The forest lays bare the nature of patriarchal social structures that support hierarchies which exploit both woman and the forest and in this regard, Sita’s return to the earth can be read as a rejection of patriarchy and an example of “ecofeminist triumph” (see Diamond 97, 89). Ultimately, Sita’s Ramayana is a combination of two distinct yet resonant readings of Sita’s predicament from two very differently-positioned women, for whom Sita carries varied symbolic significance. For Moyna Chitrakar, singing the Ramayana across the villages of Bengal is aimed at gently nudging the routinely abused, and despairing rural woman to compare the scale of her suffering to Sita’s and drawing inspiration from this perspective, to learn to face her own challenges with “humanity and compassion” (Chitrakar). Within this framework, Sita represents a gendered existential dilemma, lending grace and dignity to rural women’s suffering, with an emphasis on strategies of survival in the “navigation of everyday violence” (Krishnamurti 11-12). This is the graceful (and sometimes tearful) Sita, driven by faith, whose visual presence haunts the narrative. On the other hand, Samhita Arni has elsewhere mentioned her personal negotiation with Sita which evolved from viewing her as “a collection of virtues, the ideal woman and wife; submissive and demure” to “a complex, strong, wise woman” who displays “a great deal of sensitivity, maturity and insight”. Accordingly, Arni reads Sita’s two key trials as a rejection of her role as wife and queen and a reclamation of control over her fate—something that could speak to contemporary women in urban contexts grappling with contrary and complex social demands made upon them. This is the assertive Sita, driven by self-will, who is written onto the visuals. Sometimes, this results in slight dissonances between text and image in the graphic narrative (for instance, see Madan 327-328). Nevertheless, two women from very different contexts collaborate to invest their separate meanings into Sita’s story together, away from the conventions of a masculinist and nationalist narrative of righteous triumph and military glory, instead taking forward for a wider audience, a tradition of a counter-narrative composed by women, singing about a woman, to other women.

Conclusion

Sita: Daughter of the Earth and Sita’s Ramayana are both contemporaneous texts that centre Sita’s point-of-view in the telling of the Ramayana. In their own ways, both claim to be feminist texts speaking to a young, twenty-first-century readership even though they draw upon different visual and narrative traditions to do so and are tonally very different. If the former uneasily shifts between Sita’s identity as woman and goddess to resolve the discomfiting paradoxes in the narrative that reflect poorly on Rama who continues to be worshipped as the maryada purushottam, the ideal man and king, then the latter firmly locates Sita in the folk tradition, as an extraordinary woman with a fate that she shares with many ordinary mortal women. Both texts have varying interpretations of the epithet “daughter of the earth” that is used to describe Sita—one serves to highlight her divinity and the other emphasises her earthliness. Sita comes of age in radically different ways in these two narratives—one text ends with Sita’s satisfaction that she has fulfilled her purpose on earth as a self-sacrificing wife and queen, and the other ends with Sita’s tragic realisation that her fate is that of perpetual suspicion and abandonment from which death or disappearance is the only release. Both Sitas function in worlds of patriarchal repression that cause them much suffering, but in one, she acts in compliance with the law of patriarchy and as with Sitas before her, becomes “the agent of her own abandonment” (Chakravarti 251), and in the other, she raises unsettling and unanswerable questions challenging masculinist martial values, instead espousing an empathetic worldview in solidarity with the many victims of patriarchal violence. In the end, both texts demonstrate that Sita’s story continues to stay relevant for different, even contradictory purposes, carrying very different negotiations of ‘patriarchy and ‘feminism’ in a twenty-first-century world.

Works Cited

Arni, Samhita, and Moyna Chitrakar. Sita’s Ramayana. Tara Books, 2011.

Chakravarti, Uma. Everyday Lives, Everyday Histories: Beyond the Kings and Brahmanas of ‘Ancient’ India. Tulika Books, 2006.

Chandra, Nandini. The Classic Popular Amar Chitra Katha, 1967-2007. Yoda Press, 2008.

Chatterji, Roma. Speaking with Pictures: Folk Art and the Narrative Tradition in India.Routledge, 2015.

Dev Sen, Nabaneeta. ‘When Women Retell the Ramayan’. Manushi: A Journal about Women and Society, no. 108, 1998, pp. 18–27, www.manushi-india.org/pdfs_issues/PDF%20file%20108/5.%20When%20Women%20

Retell%20the%20Ramayan.pdf.Accessed 11 Jan. 2023.

Diamond, Catherine. ‘Four Women in the Woods: An Ecofeminist Look at the Forest as Home’. Comparative Drama, vol. 51, no. 1, Spring 2017, pp. 71–100, doi:10.1353/cdr.2017.0003.

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Penguin Press, 2009.

Jha, Varsha Singh. ‘Writing the Picture: Ramayana Narrative in a Graphic Novel Form’.

International Journal of Comic Art, vol. 18, no. 2, Fall/Winter 2016, pp. 488–502, https://ijoca.blogspot.com/2017/02/international-journal-of-comic-art-18-2.html. Accessed 16 July 2023.

Kakar, Sudhir. The Inner World: A Psychoanalytic Study of Childhood and Society in India. Oxford University Press, 1978.

Krishnamurti, Sailaja. ‘Weaving the Story, Pulling at the Strings: Hindu Mythology and Feminist Critique in Two Graphic Novels by South Asian Women’. South Asian Popular Culture, vol. 17, no. 3, Nov. 2019, pp. 1–19. doi:10.1080/14746689.2019.1669429.

Madan, Anuja. ‘Sita’s Ramayana’s Negotiation with an Indian Epic Picture Storytelling Tradition’. Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Michelle Ann Abate and Gwen Athene Tarbox, University Press of Mississippi, 2017, pp. 312–31.

McLain, Karline. ‘Many Comic Book Ramayanas: Idealizing and Opposing Rama as the Righteous God-King’. Comics and Sacred Texts: Reimagining Religion & Graphic Narratives, edited by Assaf Gamzou and Ken Koltun-Fromm, University Press of Mississippi, 2018, pp. 85–103.Nagpal, Saraswati, and Manikandan. Sita: Daughter of the Earth. Campfire, 2011.

Shah, Shalini. ‘On Gender, Wives and “Pativratas”’. Social Scientist, vol. 40, no. 5/6, June 2012, pp. 77–90, www.jstor.org/stable/41633811. Accessed 13 Jan. 2023.

Sutherland, Sally J. ‘Sita and Draupadi: Aggressive Behavior and Female Role-Models in the Sanskrit Epics’. Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 109, no. 1, Mar. 1989, pp. 63–79, www.jstor.org/stable/604337. Accessed 12 Jan. 2023.

Endnotes

iIncidentally, both books were published in the same year (2011), to much popular acclaim. Sita: Daughter of the Earth was shortlisted for the 2012 Stan Lee Excelsior Award (www.excelsioraward.co.uk/shortlist2012.html, accessed 20 August, 2023) and Sita’s Ramayana featured in the New York Times Bestseller List of graphic books in 2011 (www.nytimes.com/books/best-sellers/2011/10/30/hardcover-graphic-books, accessed 20 August, 2023).

iiAccording to Sailaja Krishnamurti’s classification of post-Amar Chitra Katha mythology-based Indian comics and graphic narratives, Campfire titles (the publisher of Sita: Daughter of the Earth) are “authenticity-driven” narratives continuing ACK’s tradition of “mythological didacticism” (4), whereas Sita’s Ramayana is an “affect-driven” narrative, more invested in engaging with complex questions of “memory, self and subjectivity” (5).

iiiOn the one hand, the Sita ideal of a pativarata woman is characterised by “chastity, purity, gentle tenderness and a singular faithfulness which cannot be destroyed or even disturbed by her husband’s rejections, slights or thoughtlessness” (Kakar 66). But at the same time, the glorification of the Sita ideal stems from a high regard for Sita’s perceived moral superiority and the dignity and grace with which she is seen bearing her fate of abandonment that remains a cause of insecurity for many Indian women (Dev Sen 19-20). If Sita is too idealistic and gullible a model of obedient and chaste womanhood for some, for others she is as “an antisuttee” (Doniger ch.9) with a defiant, if masochistic mode of protest (Sutherland 78-79).

vFor an analysis of Patua’s adaptation into the graphic narrative format, see Madan and Jha.

viSee www.womensweb.in/articles/moyna-chitrakar-sitas-ramayana /(accessed 20 August, 2023). I owe this reference to the essay “Writing the Picture: Ramayana Narrative in a Graphic Novel Form” (Jha).

viiSee www.womensweb.in/articles/samhita-arni-sitas-ramayana/ (accessed 20 August, 2023).

Issue 110 (Jul-Aug 2023)

-

EDITORIAL

- Sapna Dogra: Editorial Comment

-

ARTICLES

- Meghna Borate-Mane: Decoding Human-Animal Hybridity in Trauma Graphic Narratives

- Rani Alisha Rai: The Fluidity of Graphic Novels Through a Study of Sarnath Bannerjee’s Corridor

- Rituparna Sengupta: Goddess or Woman, Pativrata or Feminist? - Sita in Two Contemporary Graphic Narratives

- Sakshi Wason: Which ‘Side’? Displacement and Dispossession in Sa’adat Hasan Manto’s “Toba Tek Singh” and Vishwajyoti Ghosh’s This Side That Side: Restorying Partition

- Santanu Saha: Indian Women Fighting Back in Kuriyan and Das - A Comparison in Retrospect

- Sapna Dogra: Dismantling Binary Notion of Being and Telling - Queer Gaze in Kari

- Shweta Mishra: The Indian Graphic Novel - A Distinct ‘Comic’ And ‘Serious’ Text-Image Medium

- Sreya Mukherjee: City as Text, City as Palimpsest - A Critical Reading of the Urban Spaces in the Graphic Novels of Sarnath Banerjee

- Sreyasi Mitra:Nature‘s Voices - Ecofeminist and Ecocritical Perspectives in Indian Graphic Narratives

-

CONVERSATIONS

- Sneha Rita Sebastian and Resham Anand: Graphic Narratives in the Digital Age - In Conversation with Bhaghya Babu

- Sonal Dugar and Ila Manish: Drawing from the Real World - Ita Mehrotra on Storytelling from Beyond the Studio