Saeed Ibrahim

Saeed Ibrahim

The SS Vaitarna arrived at Mandvi Port on 5th November 1888. As news spread about its arrival a lot of interest and excitement was generated around the giant new ship and throngs of curious bystanders gathered on the pier side to view and admire the vessel. Instead of its official name it began to be referred to by the popular nickname of “Vijli” or electricity since it was lighted with electric bulbs, a novel feature for the time.

The ship left Mandvi port on Thursday 8th November at 12 noon with 520 passengers and 43 crew members. She reached the port of Dwarka where she picked up a further 183 passengers taking the total passenger number to 703. She left for Porbander but due to bad weather she did not stop at Porbander and headed directly for Bombay, a port that she would never reach.

Late that evening she encountered a heavy cyclonic storm with high, gusty winds with speeds of 100 miles per hour and over. The strong winds were accompanied by torrential rain and storm surges that caused gigantic waves to rise high above the surface of the sea lashing the sides of the ship and repeatedly sending it tossing upwards only to come crashing down again in a mad seesaw.

Mayhem reigned on board the ship. The screams of the terrified women and children could be heard above the crashing waves as they sat huddled together, drenched to the bone and desperately clutching each other’s wet bodies. As the ship swayed relentlessly upwards and downwards some clung on for dear life to whatever firm object they could lay their hands on, only to be dragged cruelly away by the sheer force of the wind and the rain. The harried crew members tried frantically to garner all possible help to the panic stricken and helpless passengers. But hampered by the ferocity of nature, their efforts were rendered useless.

Being ill-equipped to handle a tempest of such a devastating magnitude, the SS Vaitarna was overpowered and after a valiant battle with the stormy sea she was sadly wrecked and sank off the coast near Mangrol. The hopes and dreams of the 750 people on board were shattered and their lives snuffed out in the matter of a few hours.

The next day the ship was declared missing. The Bombay Presidency and the shipping companies sent out steamers to find the wreckage. But there were no survivors. No wreckage, no debris and no bodies were ever found. The ship had just mysteriously vanished and the bodies of all its passengers and crew consigned to a watery grave.

After the disaster, a number of questions and theories were put forth on the ship’s seaworthiness and whether adequate safety measures had been put in place. Did it have enough lifeboats and life jackets on board? Had there been any instance of foul play or a conspiracy of some kind? Was this a case involving the hand of the supernatural and in the case of Jan Mohammed and Hajra, had they been pushed to their deaths by the cryptic prophecy of an itinerant fakir? The questions and doubts remained unanswered.

News of the shipwreck and the disappearance of Vijli was slow to reach the families in Gujarat and Bombay. When it did finally get to them, it was met with shock and utter disbelief. Throngs of people gathered at Rehman and Halima’s home to offer their condolences and there were the usual prayers for the departed offered both at the mosque and at ladies’ gatherings at the house.

Aisha was devastated. Her cries of anguish pierced through the house and no words of comfort or the unequivocal outpourings of her aunt’s love could console her or assuage her grief. She began to shun the company of others, became silent and depressed and withdrew deeper into her shell. She would sit for hours by the window in her room staring at the empty sky until the fading light of the setting sun cast deep shadows over the roof tops of the surrounding buildings. Sometimes she would look down to the street below and see the lamp lighter on his daily sunset rounds armed with his tall ladder as he went around from street to street lighting up the gas lit lamp posts in his locality.

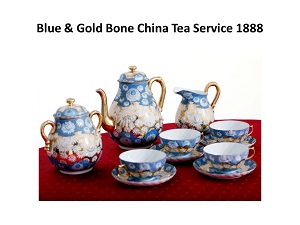

The steady stream of sympathisers and well-wishers, and the letters and messages of condolence continued to pour in. The 40th day, marking the official close of the mourning period, arrived and went by. Aisha remained locked in her grief, until one day towards the end of December, her uncle Rehman announced that a consignment of goods had arrived in Aisha’s name from the distant shores of England. It was the bone china tea service that her father had ordered for her. It was a beautiful blue and gold lined set of the finest egg shell china with six dainty cups and saucers, a large and elegantly shaped tea pot, milk jug and sugar bowl and half a dozen dessert bowls and an equal number of side plates.

Overwhelmed by the arrival of this unexpected, posthumous gift from her parents, her spirits lifted as she felt engulfed by their presence around her. She carefully picked up and fondled each piece. Where other attempts to console her had failed, this symbol of her parents’ great love for her, finally brought her the comfort and solace that she had so far blocked out. Gradually over the following weeks the colour began to appear back on Aisha’s face and she started participating in the family’s activities. Orphaned at the age of 16 years, the void left by the loss of her parents remained with her throughout her life. But with the unstinting love and support of her family she began to face life with more equanimity and a kind of resigned peace now descended upon her.

N.B. The full unabridged version of “Twin Tales from Kutcch” is available in both paper back and Kindle forms on all Amazon platforms worldwide.

|

|

Issue 103 (May-Jun 2022)

-

RESEARCH PAPERS and ARTICLES

- Aalisha Chauhan: Postmemorial Writing of Trauma: A Therapeutic Healing through Selected Poetry of Rupi Kaur

- Manjinder Kaur Wratch: “The Wound is the Place where the Light Enters”: Reading the Legacy of Prejudice and the Memories of Human Bonding in Githa Hariharan’s Fugitive Histories

- Noduli Pulu: The Dissonance between Veracity and Memory in Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost

- Parminder Singh : Digitization and Exhibition of the Cultural Treasures of Punjab: A Case Study of Panjab Digital Library

- Priyanka Verma: Food as Cultural Memory: A Reading of Tomatoes for Neela

- Saeed Ibrahim: MEMORY AND MEMORABILIA - The Inspiration Behind My Book “Twin Tales from Kutcch”

- Vidit Jain: Restoration versus Destruction: Libraries as Cultural memory Markers

-

SHORT STORY

- Harpreet Kaur Vohra: Warm Socks

-

POETRY

- Mohd Sajid Ansari

- Nidhi Rana

- Parminder Singh

- Praveen Kumar

- Sunaina Jain

-

BOOK EXCERPT WITH an INTRODUCTION

- Saeed Ibrahim: Extract from the Book Twin Tales from Kutcch

- Editorial

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL

- Editorial

- EDITORIAL