Akanksha Pandey

Akanksha Pandey

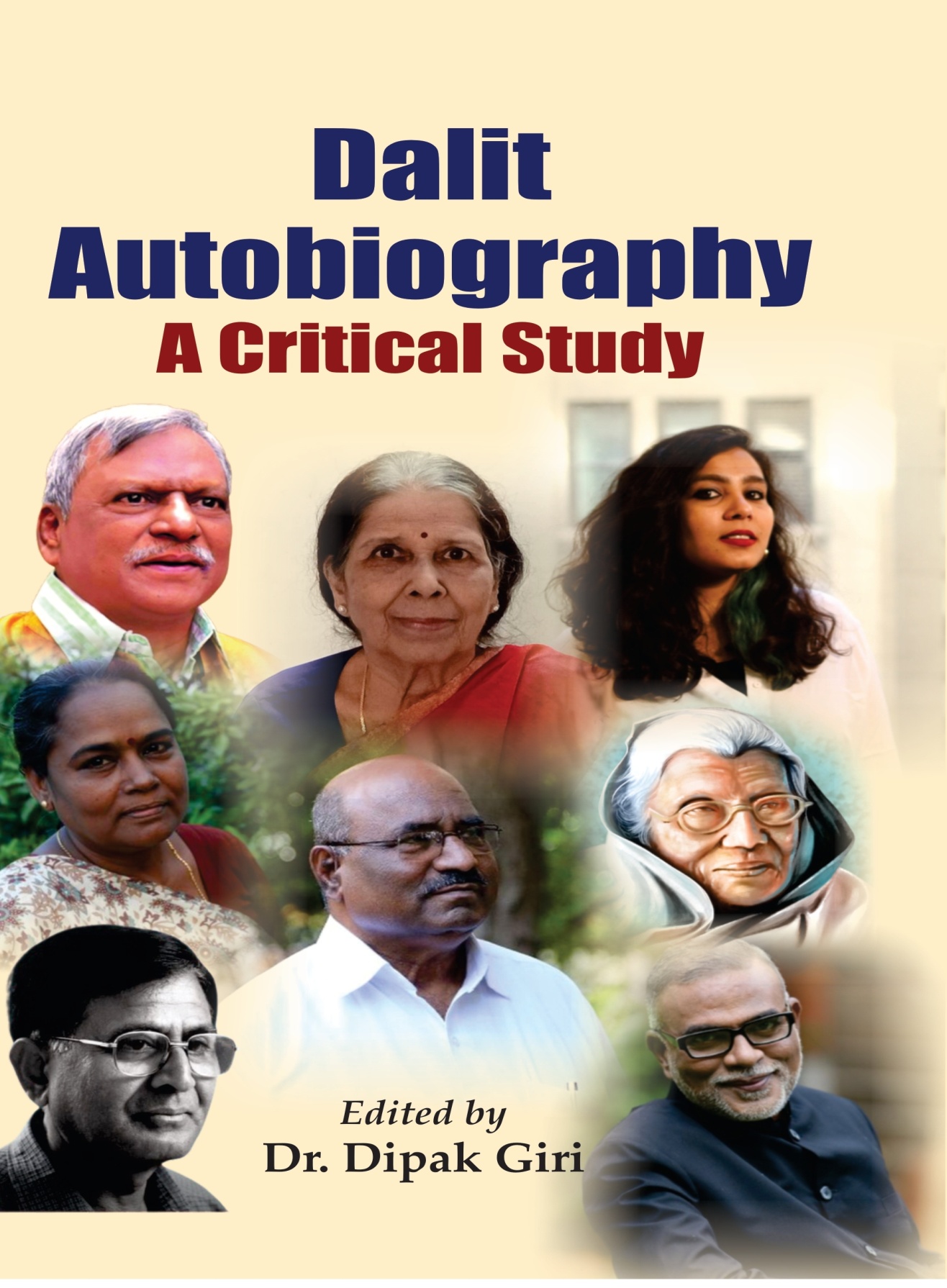

Dalit Autobiography: A Critical Study| Non-fiction| Dr Dipak Giri (Ed.)|

New Delhi: Rudra Publishers & Distributors (2025)|

ISBN: 978-93-48421-19-7 |Pp 266|₹1,190

Dalit Autobiography: Resisting Erasure, Reclaiming Truth

Dalit Autobiography: A Critical Study, edited by Dr Dipak Giri, is a very crucial addition to Dalit studies in India. This book, being the second publication, as far as Dr Giri’s contribution towards Dalit studies is concerned, appeared next to Perspectives on Indian Dalit Literature: Critical Responses which was published from Booksclinic Publishing in 2020. Contrary to his earlier book Perspectives on Indian Dalit Literature which is a study of Dalit literature in general, this present book Dalit Autobiography is particularly related with the personal history of many Dalit writers and activists. The book’s cover page underlines the motive of the book and suits the title Dalit Autobiography: A Critical Study. The intention behind depicting different Dalit individuals on the cover page is to inform that this collection is going to be related to the concerns of Dalit community. It will help to enrich Dalit literature as people from diverse backgrounds will come to this front for a same cause.The uniqueness and diversity of their experiences are highlighted. It is a thoughtful presentation and not just a random assortment of faces. This book serves as a critical examination of Dalit autobiographies which establishes a powerful and thought-provoking interface.

Such autobiographies, with hardly any room for imagination—are realistic and convincing, are always welcoming and enduring to academics and scholars who wish to do further studies in this specific area; display genuine concerns like the history, culture, socio economic state, psychological state, need for political freedom and assertion of identity associated with Dalit life and individuals; are the record of their power and agency; help to understand and establish inter-relationships between all marginalised communities which help to gain a holistic understanding of the system of oppression; and also give way to analyse subaltern culture and challenge caste discrimination.

Dr Dipak Giri, being well-experienced in bringing out such collections as one can see his publication history, here also in this book, similar to his many other past publications, has applied his critical insights, both as an author and editor, in presenting the social, cultural, and political experiences that Dalits have to face and are still facing.

The introduction portion clearly elucidates the purpose of Dalit Autobiography which is not commercialization but using personal narratives as a weapon to intensify their cause and put up a question on caste relations in the society. It states that “Dalit autobiography is not meant for self-gratification or self-glorification, but as a weapon for creating a social change and awareness in an unequal society” (p. xv). In contrast to mainstream autobiographies, as Dr Giri observes, these personal records emphasize the shared social and cultural experiences rather than being a tale of interpersonal emotions, “The awareness of self, suffering of self, narration of self, in coordination with reality is what formulates Dalit autobiography…” (p. xv).

This critical analysis significantly enhances the comprehension one has of Dalit Autobiography in specific and autobiography as a genre. It is very important because this genre has, as stated by K Satchidanandan, “become a major subject of research and debate” (p. xv). It is a record of the Dalit history, pain, progress, resistance and resilience. The book encapsulates how these narratives transform themselves from being an individual to a collective voice.

This collection of twenty-four essays encompasses an array of autobiographical narratives written by acclaimed authors who in their own way define the Dalit’s experiences in totality as well as individual existence. Sharankumar Limbale’s Akkarmashi (The Outcaste), is studied by Dr Ranjana Sharan Sinha and Gobinda Bhakta to show the themes of isolation and identity crisis in Limbale. Babytai Kamble’s two books Jina Aamuch (Our Life) and The Prisons We Broke are analysed by Harish Mangalam, Dibpriya Bodo, and Dr Priyadarshini Chakrabarti to depict the different ways in which Dalit women are made to suffer. They are exploited via multiple social evils such as casteism, gender bias and class system. Dr Pramod Ambadasrao Pawar's Resilience is also appreciated for its unconventional and deconstructive view on issues such as caste and identity. Bama Faustina Soosairaj’s Karukku is the most researched and loved amongst all and has contributions from Dr Samina Azhar, Dr Supriya Mandloi, Dr Sana Farooqui, and Sayani Roy to portray casteism, gender violence and other experiences that disrupt harmony of the society. Dr Amitava Pal’s analysis of Yashica Dutt’s Coming out as Dalit: A Memoir details the protagonist Dutt’s journey to reclaim her Dalit identity. Dr Sindhu V Jose does a close textual and thematic analysis of K Elayaperumal’s The Flames of Summer. Dr D S Narayankar and Abhijeet Ghosal examine Shantabai Kamble’s autobiography Mazhya Jalmachi Chittarkatha (The Kaleidoscope Story of My Life). Bolloju Baba analyses Dadala Raphael Ramanayya’s My Struggle for Freedom of French India – An Autobiography to pave way to acceptance and appreciation of Dalit contributions. P Kamalesh Kumar and Dr C Vairavan elucidate the role of Rajgowthaman’s Kalachumai and Siluvai Raja Sarithiram in fostering cultural reclamation. Kawya Pandey and Dr Rafraf Shakil Ansari have closely examined Manoranjan Byapari’s Interrogating My Chandal Life and highlighted the impact that the partition of Bengal and Bangladesh had on Namasudra Dalit community. Dr Amima Shahudi delves into how Y B. Satyanarayana’s My Father Baliah reflects on the struggles of generational trauma of Dalits. Kanika Sharma writes on Shilpa Anthony Raj’s The Elephant Chaser’s Daughter for Battered Woman Syndrome. Ankan Biswas’s paper underlines the pain of Dalits as depicted in the powerful text by Kancha Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not a Hindu. At the end, like a dot to the perfect chain of essays, Dr Dipak Giri writes how Daya Pawar’s Baluta underlines the identity conflict of Mahars which was also the caste of Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar. Vishakha Kumari Yadav's paper also clearly evidences the discrimination inflicted on Dalit community.

This collection of essays critically examines several interconnected themes that are necessary for comprehension of the Dalit life and their contributions to the field of literature. The main tenet is the significance of Dalit autobiography itself, which is a purposeful and well thought effort to mirror the ways in which caste discrimination hollows the individual as well as social experience. It aims to measure as far as it can. The struggles and agony of marginalised reflect upon our role in their trauma. It also shows that unity works wonders and is a call for help to entire humanity. The book underlines the root causes of this pain as well as the agency and resilience of the community. Females are doubly marginalised due to casteism and gender-based discrimination. There is defiance to the oppressive rule and strategic plans to rise above these shackles made by society. They are very rich in their traditions and each culture in India is linked to another but the mainstream sidelines the culture of Dalit. This book brings forth this realisation as well. It re-defines Indian literary traditions. It outlines the role of history and negligence of the plight of marginalised communities and the essential contributions of educators and social reformers of Dalit community like Dr B R Ambedkar in initiating the quest for empowerment and respect. It is also a critique of the cultural, societal practices that sustain caste hierarchy, supporting the genre’s function in raising a question on the injustices inflicted by the system and its failure to attend to such cases where human rights are majorly involved.

This collection of essays plays a very important part in expanding the literary canon, helping to firmly establish Dalit autobiography as a distinguished and unique genre, which while advocating for its essence within the Indian English literature, broadens the field of literary studies on a global stage. It voices subaltern concerns, giving them a platform from which they had been pushed down, insulted and barred only to maintain the impression of them being voiceless. Dalit autobiographies resist the conventional literary normal by retaliating against the standard narrative structures and linguistic boundaries. It seeks to promote greater standards which are new and of quality. The critical analyses presented in this book promote such socio-literary discussions which encourage to take a dive in the ocean of co-existence and interdependence of literature and social change for which Dalit autobiographies serve as a fundamental example since it has in its essence, the call for realisation and action. The stories go beyond personal interest and reach out to global audience in the form of being a source of national and international interest. This volume raises issues that are necessary to bring harmony in the society. By a thorough reading of a spectrum of autobiographies, as well as investigation of the same book by varied lenses offered by different academics, it allows to enrich Comparative Studies, Regional Studies and Multicultural Studies while simultaneously exploring the universality of themes such as oppression, resistance, power and agency. Such works have been translated into several languages and are being studied throughout the world. They invite new researches and continued inquisition. Therefore, such kind of volume was necessary to be brought out to the front.

Dalit Autobiography: A Critical Study transcends being merely a collection of essays. It serves as a compelling testament to the enduring spirit of the Dalit community and an essential academic resource. It compiles numerous significant essays carefully curated by the editor. It not only illuminates the distressing realities of caste discrimination but also honours the resilience, intellect, and literary talent of those who have been historically marginalized. The aim of the editor and contributor Dr Giri as stated in the book— “Hopefully this anthology as a plea for this community of people who have long been devalued and derogated under the caste hierarchy serves largely to society and mankind” (p. xxv)—holds truth value. For anyone interested to expand their understanding on Autobiography as a literary genre and social tool, South Asian Literature, Postcolonial Studies, World Literature, Subaltern Studies, or the wider conversation about social justice through literature, this book is a must read, encouraging readers to contemplate societal inequalities and the influence of individual narratives on collective consciousness.

Issue 123 (Sep-Oct 2025)

-

EDITORIAL

- Sukanya Saha: EDITORIAL

-

REVIEWS

- Akanksha Pandey: ‘Dalit Autobiography—A Critical Study’, Ed. by Dr Dipak Giri

- Jagdish Batra: ‘Who is Raising Your Children?’ by Rajiv Malhotra

- Sachidananda Mohanty: ‘Yellow—Poemlets New & Earlier’ by Sukrita

- Sudha Rai: ‘Silver Years—Senior Contemporary Indian Women’s Poetry’, Ed. by Sanjukta Dasgupta, Malashri Lal, Anita Nahal

- Sutanuka Ghosh Roy: ‘Yatra—An Unfinished Novel’ by Harekrishna Deka (Assamese original), Trans. by Navamalati Neog Chakraborty

- Yater Nyokir: ‘Tales from the dawn-lit mountains’ by Subi Taba