Aparna Singh

Aparna Singh

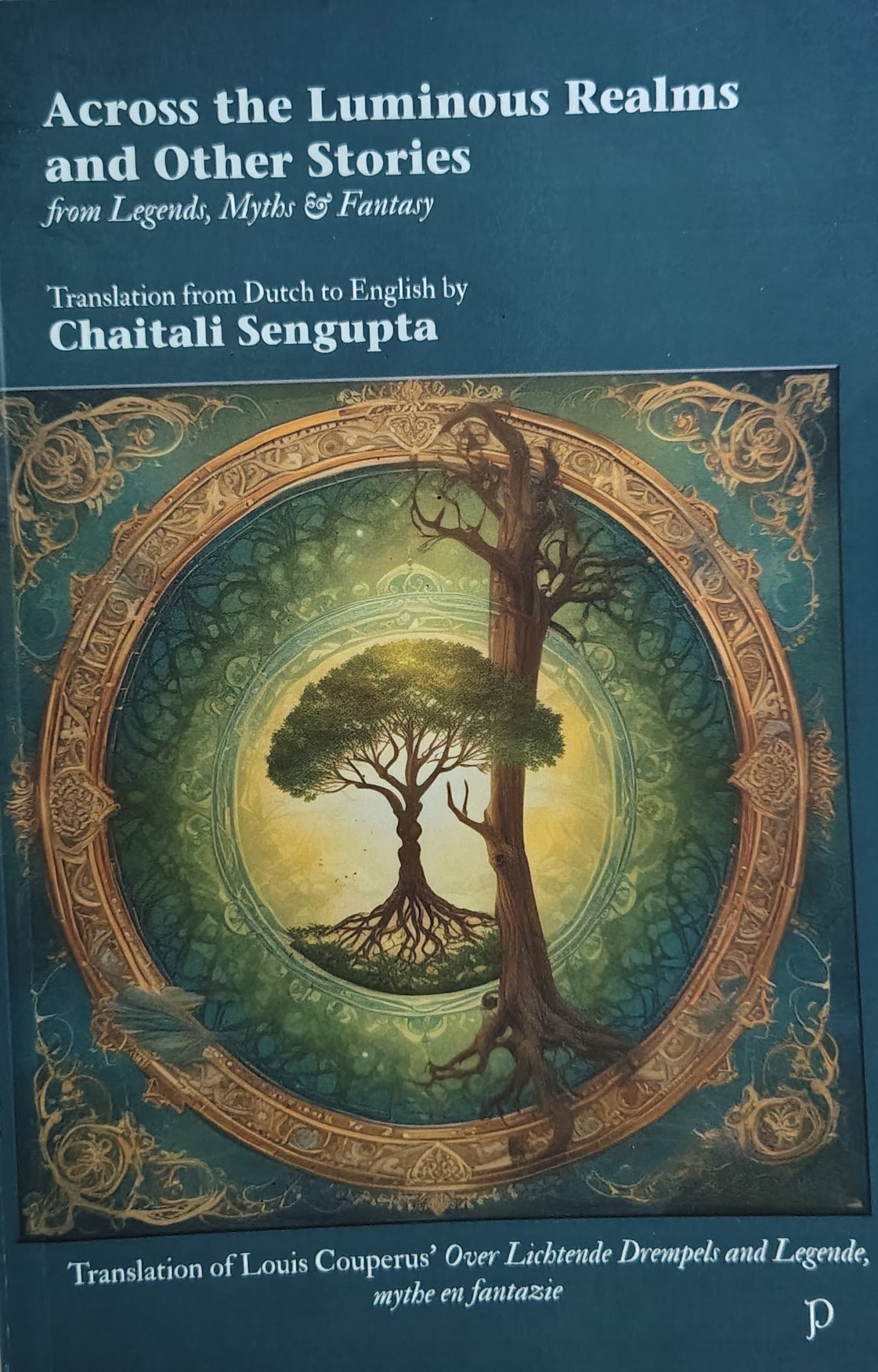

Across the Luminous Realms and Other Stories | Fiction | Louis Couperus (Dutch original) | Trans . by Chaitali Sengupta | Penprints (2025) | ISBN: 978-81-981564-8-8 | Paperback | Pp 204 | ₹500

Weaving History, Symbolism , and Fantastical Narratives

Across the Luminous Realms and Other Stories, from Legends Myths and Fantasy is a translation from Louis Couperus’s Dutch Over Lichtende Drempels and Legende, mythe en fantazie, into English by Chaitali Sengupta. Sengupta picks a novella and four fairy tales (Couperus wrote as a gift for his wife) to introduce the book to a new readership. Couperus’s Legende, mythe en fantazie (1918) is a collection of seven short stories blending history, myth, legends, and fantasy, drawing from various cultures and historical eras. These stories share common themes of ancient wisdom, spiritual seeking, and his theosophical belief in the oneness of the soul. They weave historical contexts with rich symbolism and imaginative narrative, blending fantastical tales from various cultures and historical eras.

Victor van Bijlert, in his introduction to the book, lauds Sengupta’s linguistic felicity and her skilful handling of the “unyielding Dutch” that comes across as smooth and readable in English. The linguistic gaps she navigates as a translator, however, must have been intimidating at times since the book’s archaic and extinct old Dutch challenged the level she had learned at the language school.

Louis Couperus (1863–1923), a writer rooted in theosophical and mystical thought, integrates hidden spiritual meanings into his works. His stories reveal a world where the physical realm is just the surface of a much deeper spiritual reality. Sengupta captures this complexity by preserving the fable-like quality of the tales while ensuring their philosophical depth remains intact. Sengupta undertakes the formidable challenge of translating not only the Dutch language, steeped in archaisms and symbolic density, but the cultural and psychological substratum encoded in Couperus’s prose. Her rendering achieves more than linguistic clarity: it revitalises Couperus’s mythopoeic imagination for a contemporary, multicultural readership. With her multilingual background, she is particularly attuned to what Carl Jung termed the collective unconscious—the reservoir of shared symbols and motifs that transcend individual cultures and tap into universal human experience.

Over lichtende drempels en andere verhalen blends fairy-tale charm with a subtle exploration of esoteric ideas. Departing from the traditional, conventional storytelling formats, “these four fables maintain a fairy-tale quality while quietly reflecting on reality without moralising … a thought-provoking journey of the collective imagination”, says Sengupta. She further states that Couperus’s work offers something for everyone, and she was “struck by his ability to weave historical context with rich symbolism and imaginative narrative revealing deeper, often mysterious layers of human experience.”

In the fable “The Princess with the Blue Hair” unveils princess Yweine’s possessive desire to keep her “flowing, rippling … enchanting blue hair” to herself, quite in contrast to her altruistic father who generously tore his royal purple cloak into small shreds and scattered them “among the people in grand ceremonial gesture.” This vain indifference saddened the king as he wished Yweine could distribute it among the hungry people, as it would “bring health, happiness, prosperity, and love to our good people.” By a sudden turn of events, the Princess falls ill and eventually, with the intervention of a young magician, she is awakened to the kindness in the redeeming act of donating her erstwhile precious hair. The story ends with “… a wave of joy spread throughout the kingdom, lasting for many years to come.”

Seamlessly translated, Sengupta infuses the original with a tender, flowing register. In the next fable titled “From the Crystal Towers,” the following lines stand out for their resplendence:

“Her light green eyes resembled the soft flow of a brook winding over moss. Her pale, golden hair cascaded like moonlight flowing over water. Her smile was as wistful as a cloud drifting across the moon.”

The fable recounts the tragic union of two siblings cruelly separated by their parents, Merlin and Morgueine. Little Irene is nourished by the milk of the lilies as her father “traced a circle through the air, sealing Irene’s fate.” Growing amongst the lilies, wandering through the shadowed parks, she grew up lonely and forlorn. Although her voice “rang out like pearls, trailing the soft, golden strings of her harp,” she craved for a companion, a soulmate. She is directed by her nurses, the lily-elves, to look for her brother, subject to similar confinement. Finally, they both unite in death with the resounding hope—“But love never dies…” A powerful meditation on relationships, the fable finds a fitting home in the English version, evocatively and deftly crafted by Sengupta’s clear-eyed, richly textured prose.

In the novella “Across the Luminous Realms,” Couperus unearths complex family dynamics where a woman tethered to her deathbed is torn apart by the desire to unveil a secret box filled with love letters from her lover. They weigh heavily on her, but much as she wishes, she fails to share them with her children Alma, Lilia, and Stella. It is only after her death that Lilia stealthily reads those letters and comes upon the guarded, clandestine secret of her birth. The story follows the tragic trajectory of acceptance and reconciliation her husband undergoes, having encountered this hitherto unknown aspect of his wife’s life. The spirit of the dead woman (accompanied by her lover) hovers between guilt and atonement, the liminality between earthly shackles and heavenly transcendence. Redeemed by forgiveness, the husband finally overcomes his initial hatred for Lilia and acknowledges her as his own— “Yes … I forgive you …Call me father … Forgive me for I forgive your mother.” Unburdened by emotions now unleashed, the mother’s restless soul is finally set free—their spirits… separating from their bodies. The next story, “Of Days and Seasons” is a poignantly lyrical reflection on the asymmetrical trade-off between life and death, camouflaged, as it is, by overweening desires.

Sengupta’s translations elevate the source texts beyond literal rendition; her intuitive grasp of rhythm, cadence, and metaphor infuses the prose with an ethereal quality that resonates with Couperus’s mystical aesthetic. Her choices in diction and imagery reflect both restraint and imagination, crucial in preserving the tales’ symbolic density. The collection, comprising one novella, four fairy tales, and seven short stories, reveals a thematic continuity, exploring transformation through suffering, the tension between individual desire and communal well-being, and the possibility of transcendence. Sengupta’s translation subtly underscores these shared motifs, allowing readers to trace the spiritual arc that threads through Couperus’s diverse storytelling modes. By reanimating Couperus’s tales for a global audience, Sengupta contributes to a broader revaluation of under-translated European modernists. In an era where translation is increasingly viewed as a political and ethical act, her work stands as a model of translational empathy and literary flag-bearing. It demonstrates how translation can function as a bridge, not just between languages, but between epochs, cultures, and systems of belief.

Issue 122 (Jul-Aug 2025)

-

EDITORIAL

- Sukanya Saha: EDITORIAL

-

REVIEWS

- Aparna Singh: 'Across the Luminous Realms and Other Stories' by Louis Couperus (Dutch original), Trans. by Chaitali Sengupta

- Dhrishni Saha: 'Money Doesn’t Grow on Trees' by Lavanya Mohan

- Himank Garg: 'Nocturne Pondicherry—Stories' by Ari Gautier (French original), Trans. by Roopam Singh

- Madhavi Latha: 'Indian Diaspora Literature—A Critical Evaluation', Ed. by Dipak Giri

- Sachidananda Mohanty: 'The Scrapper's Way—Making it Big it in an Unequal World' by Damodar Padhi

- Sapna Dogra: 'Indian Short Story—A Critical Evaluation', Ed. by Dipak Giri