M.K. Sudarshan

M.K. Sudarshan

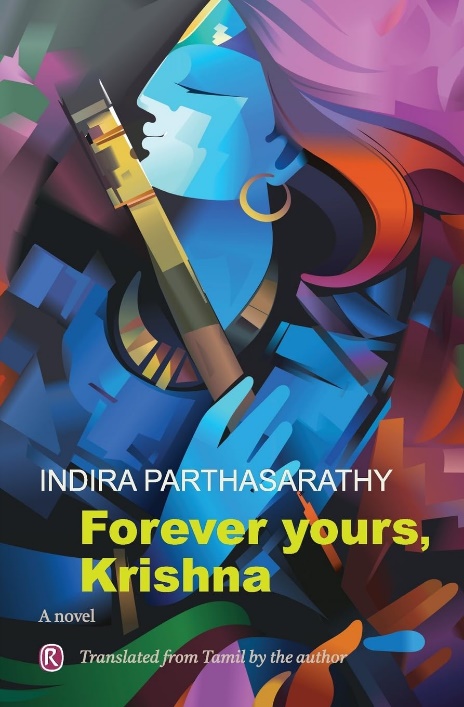

Forever Yours, Krishna : A Novel | Indira Parthasarathy |

Translated from Tamil by the Author himself | Ratna Books, New Delhi (2024) |

ISBN 978-93-56873-65-0 | Paperback | Pp. 242 | Rs. 559

A masterful blend of diverse tales

The Sahitya Academy, Sangitha Nataka and Padma Shri Award winner for Tamil Literature, Indira Parthasarathy translated into English his own earlier Tamil novel with the endearing title “Forever Yours, Krishna”, first published in 2006 and now reprinted in 2023. The book is indeed an extraordinary mixture of many stories taken from the purana and itihaasa genre of India, all culled from the Hindu scriptures such as the Harivamsham, Srimad Bhagavatham, Vishnu Purana, and the Mahabharatha. The book, rooted in India’s epic scriptures, may confuse English-speaking foreigners unfamiliar with Hindu classics like the Puranas and Itihasas. They teem with just too many events and characters. This novel narrates almost all of the main ones without exception. This novel adheres closely to the Mahabharata but assumes prior knowledge of its context and characters.

Parthasarathy retells Krishna’s biography with vivid drama, exploring complex themes and moral ambiguities. According to the Mahabharata and Bhagavatam, Jara, a forest hunter, unintentionally inflicts a mortal wound on Krishna in the final days of his earthly incarnation. As Krishna lies dying, he recounts his life story to Jara.

“I want you to narrate my story, defining the significance and essence of my role during this lifetime of mine, so that generations that come thousands of years later will be able to understand me and relate to me in another time and space”.

As Jara departs, Sage Narada approaches, eager to learn about his pivotal meeting with Krishna. Jara shares the profound words Krishna spoke in their final moments together.

“Krishna narrated his story to me and asked me to tell it to others. I feel that his story needs to be told in a language which can always be understood and that you are the right person to do it because you are the eternal cosmic traveller. You are in a position to spread the story of Krishna, I shall tell it to you word for word, and you can compose it in your own language and narrate it to others. This is my humble request”.

Indira Parthasarathy channels Sage Narada, retelling Krishna’s tale with artistic liberty. This narrative device allows him to reimagine Krishna’s story for future generations.

Parthasarathy’s Krishna is a complex figure, wielding politics and subversion with calculated precision. Krishna’s character mirrors Leon Trotsky “Revolution is permanent”. Contextualizing this quote within Hindu culture reveals Krishna's divine avatar, motivations, and daring exploits. Parthasarathy exemplifies a rare sort of divinely ordained and sublimated Social Anarchism using many of Krishna’s avatar exploits.

Krishna’s early life in Gokulam and Brindavan challenges traditional patriarchy, advocating for gender equality. He frolics and flirts with the “bhakti” besotted Gopika cow-maidens in his community and draws them all out of their deep-seated feminine inhibitions and self-stereotyping. He gives them the true joy of living and liberates them from the shackles of conventionality. In the sexual mores of Krishna’s and Kunti’s times, polygamy and polyandry were both not uncommon. Today both are taboo in modern society. Both are thematically explored however by Parthasarathy in starkly bold and candid terms. But Parthasarathy stops well short of going far enough to push the boundaries of his explorations of a sexual ethic which, in the time of the Mahabharatha, might have prevailed only by exception amongst ruling or wealthy classes but was never normative even then amongst commoners. Sexual ethics were then as influenced by class and caste consciousness as they are even in the contemporary age.

Then there is the fascinating story of how Krishna overthrows the tyrannical rule of his uncle, Kamsa, and fights a long-drawn struggle for political power with the entrenched establishment of the dominant, ruling classes and Kshatriya castes in Bharathavarsha. There are twenty-three chapters in Parthasarathy’s novel and most of them are grippingly retold narratives of how Krishna plied his trade as an “andolan jeevi”, a politician who was a master of covert constitutional subversion.

There are very absorbing narrations of how Krishna employed all manner of guile, vile, stealth, deception, stratagem, dissimulation, sleight-of-hand, ambush, and dharmic skullduggery to defeat his adversaries, outwit, outguess, outmanoeuvre and overcome them. Several inter-leavened, overlapping narratives tell the story of how tyrants, asuras, villains, rapists, fraudsters, thugs, and kleptomaniacs were all humbled and destroyed, one after another, by Krishna. This narrative takes a thrilling ride through the life of Krishna, the cunning and powerful politician-king of Dwaraka. The list of his power struggles against his adversaries is long and colourful indeed --- Kamsa, Jarasandha, Rukmi, Kalayavana, Sisupala, Narakasura, Banasura, Paundaraka, Satrajit, Bhisma, Drona, Radheya, Duryodhana…. It ends with the great War of Kurukshetra which signalled the death knell of a great Yuga, an era in the affairs of mankind itself called “Dvapara Yuga”.

Indira Parthasarathy’s Krishna embodies the Creative Anarchist's philosophy, revealing a fresh perspective on the divine avatar. Krishna’s story, according to Parthasarathy, characterizes much of the fundamental culture of India where, to this very day, so many equally self-destructive Kurukshetra-like wars --small and not so small - are being fought every day and everywhere in the far corners of the country – with every one of them being speciously called as a veritable “dharma yuddha”. The battles in India today are being continuously fought not on any bloody killing fields of Mahabharata Kurukshetra but in equally vicious, virulent political theatres of engagement where caste, power, dominance, the might of money-power, the cut-and-thrust, the din and bustle of no-holds-barred, no-prisoners-taken socio-political conflicts are now part of everyday life and the daily narratives of 24/7 daily TV-news channels.

It was Krishna thus - as Queen Gandhari of Hastinapur, correctly assesses him in Parthasarathy’s delightful novel, who first laid out the cultural template for even modern Indian political architecture. It is from Krishna’s own life and exemplar exploits that today the basic pattern in which the anarchically functioning life of the Indian peoples has been set and is being led, conducted, and sustained.

To Krishna of the Mahabharata, the sum of all human existence was nothing, but the perennial struggle between good and evil - an endless strife to gain wealth and power by arrogant men with vaulting ambitions and hubris. As he lay dying in Dwarka, Krishna’s final words to Jara, the hunter, were deeply self-introspective and gloomy when he spoke about how his very own clans of the Yadavas much like the Pandavas and Kauravas too destroyed themselves:

“They waged a destructive war, or shall we say, committed “collective suicide”, mindlessly killing one another in a frenzy... Power and wealth corrupted us, made us arrogant and we deserved to die; you may call it destiny or give it any name you like. The combination of the arrogance of power, the greed to amass wealth and the dissipation of wealth has always been the cause of the disintegration of society. That is what history teaches us….”

The Mahabharata era was marked by moral decay, corruption, and cynicism. Krishna, too, was influenced by this zeitgeist, embracing moral relativism over idealistic absolutism.

- “I’m an anarchist, a rebel. I do not believe that there is any absolute code of conduct which is valid for all time….

- “According to the law of the jungle, the strongest have all the privileges”.

- “Life is a game. There are certain rules to be followed. You either follow them or violate them. …

- “Dharma is a path. The path you choose in accordance with your circumstances is dharma. …The interest of the game depends upon the choice you make. It is this (moral) contradiction that makes the game interesting.

- “The ideological and emotional conflicts within us (which we grapple with as we make our choices) provide meaning and relevance to our lives. These are the rules of the game of life; we have to play according to set rules. There is no exit….”

Issue 118 (Nov-Dec 2024)

-

EDITORIAL

- Sukanya Saha: Editorial

-

REVIEWS

- Aparna Singh: “Anemone Morning and Other Poems” by Gopal Lahiri

- Kashmi Mondal: “Beneath the Simolu Tree” by Sarmistha Pritam

- Kawshik Ray: “A Short History of Australian Literature” by Paul Sharrad

- M.K. Sudarshan: “Forever Yours, Krishna - A Novel” by Indira Parthasarathy

- Madhulika Ghose: ‘The Girl with the Seven Lives – A Novel’ by Vikas Swarup

- Sapna Dogra: “From Pashas to Pokemon” by Maaria Sayed

- Semeen Ali: Scent of Rain: Remembering Jayanta Mahapatra edited by Ashwani Kumar

- Sutanuka Ghosh Roy: “Dwellings Change” by Ramapada Chowdhury