Aparna Singh

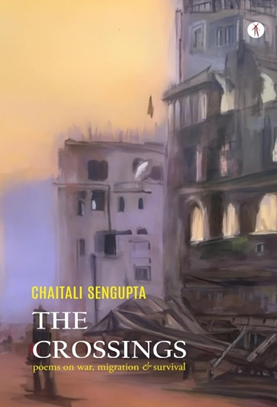

The Crossings | Poetry | Chaitali Sengupta |

Hawakal Publishers (2023) | ISBN: 978-81-963974-6-3 |

Paperback | Pp 119 | Rs 400

Poems that map the complex historical, mythical and ideological trajectory of power and powerlessness

Chaitali Sengupta writes and translates fiction, poetry, and non-fiction. The Crossings, her second poetry collection, envisions a world around war, migration and survival—the three sections into which these poems are neatly divided. Bashabi Fraser, in her insightful foreword to the collection, writes, “The impact of conflicts on individual lives is powerfully captured in poem after poem [...]” Sengupta’s stark bristling anger strikes us at the very onset, “And then, one day they left. Castrating our future with sterilized guns”.

Judith Butler in a recent article on violence and the condemnation of violence, says “The matters most in need of public discussion are those that are difficult to discuss within the frameworks available to us.” The trauma of war and displacement far supersedes the existing linguistic templates. The Crossings reflects Sengupta’s deep awareness and negotiation of this very lack. It also creates a much-needed space—an intergenerational one—shared and collective, for such experiences to be articulated.

The poems map the complex historical, mythical and ideological trajectory of power and powerlessness that is rooted in colonialism, xenophobia and cross-border politics. Sengupta puts it succinctly, “The circumstances in which the migrants were forced to depart their home countries—be it Syria, Afghanistan, Venezuela or Ethiopia—were brutal, to say the least.” When “hell is white […] as white as the smoke screen” in the arbitrarily titled “Sometimes Hell is…” one can only marvel at the vivid wordplay Sengupta delves into, drawing the readers into an abyss of irreparable loss.

These poems alert readers about the more recent images on television of the hundreds and thousands of Ukrainian refugees trudging through the snow, fleeing the destruction of their homes and cities by the invading Russian army. It accompanies the sinking realisation that they might never be able to return to their lives.

An immigrant herself, Sengupta's poetic sensibilities are aligned with the “rights of undocumented migrants” in the Netherlands. In the preface, she talks about her experience of working as a volunteer translator in an organization that worked for the rights of migrants. While working on the articles for translation, she realised how devastated these migrants felt while searching for an identity “beyond the borders of one’s own country”. Conflicts, their ensuing displacement, and loss of moorings can be ravaging, both physically and psychologically. They leave indelible scars. The victims at times don’t have a vocabulary to fall back on while voicing their traumatic experiences. Sengupta’s poems unhinge these fault lines as much as they explore the borders that make and unmake human experiences.

When Sengupta digs deep into the unborn child’s plea in “The Unborn’s Plea”, the words vacillate between inchoate musings and tentative resilience that comes with the struggle to survive:

My unborn voice is a whisper, as I clasp to her insides, /tensed, paralysed…

… She clasps me then, as a last treasure,

a gurgling groan, pleading for mercy.

In “1971, Noakhali”, Sengupta reimagines the experiences of her parents and grandparents. The first line encapsulates the aftershocks of communal riots that peaked during the Bangladesh liberation war. The brutally abrupt disjuncture seeded in their memory explodes like landmines, buried and hidden, yet devastating when triggered. Sengupta recreates the deep-seated agony of partition survivors, who have not been able to outgrow the traumatic shadow perennially cast over them. Often the lines are simple, rather deceptively - “What happened to Maya, my daughter?” leading to the shockingly resonant “Draping/ a hand over her breasts. Raped, like her land.” Her preference for the overtly ironical is also politically aesthetic, for example, when in “The Jagged Line of 1947” she says, with effortless precision - “The strong white fingers pencilled a jagged line on our map. The Radcliffe line. In one fluid motion, / drew a wounded territory. And the sweep of sky/ above me turned cursive.” The brief cartographical detail is pertinent, as it foregrounds how maps assert and undermine authority. They also defend, challenge and reevaluate identity. The colonial nations may have lapsed into imperial amnesia, but the former colonies cannot. In “Lost Paths”, the speaker fails to “search through the far forgotten time, a home that stood/ next to a river that flew past those verdant fields” as space and time coalesce.

Some of the poems that follow (“Without a Name”, “War and Me”, “Counting Wars”) are premised on the unresolved traumas and unprocessed emotions around the debilitating impact of war. Sengupta has an uncanny ability to pare down violence to its basics, often with intimidating details that relentlessly latch onto our reading memory. The events that she speaks of in “Counting Wars” stand out for the tragic normalization of violence. People are killed in their gardens, and the children in their schools. She then goes on to show how these cruel realities get reduced to fleeting inconsequential numbers to be mindlessly flashed on social media and television screens.

In “Behind the Barbed Wires” the sheer helplessness of the migrant, waiting for his/her turn long behind the barbed wires is etched with distinctive sharpness. Sengupta’s keen perceptiveness transpires in her sensitive reference to not only the “vacant faces, broken bodies, littered away” but the “abandoned dogs and peeling walls,/ forgotten by destiny”. We witness these migrants being “whiplashed” by “laws”, that turn draconian for refugees. Just as the pain mounts into a poignantly visceral one, Sengupta whips up the wistfully magical “Homelessness”:

Once they had a home, they tell me

in a far distant land, where May the

Wind danced upon the green fields,

ripening under the bounteous sun.

In “Why?” she unapologetically asserts the migrant’s identity as legitimate, a legal ramification of an inescapable political disorder, as legal as being human itself. Her genuine concern for the hapless refugee surfaces when she nonchalantly asks: “... do my wounds and my scars, not qualify me as a refugee? … is it my choice to become a refugee?”

In the final section, Sengupta weaves hopeful dreams into stories of survival. In “To Find Another Home” the migrants carry the smell of war on their breath like “fungus clinging to old bread”. The poems encompass separate emotional exilic states prying the liminal space between an earlier self and the self that is lost between the home left behind and the search for a new one; to belong without being judged.

The Crossings is unflinching in its portrayal of violence, loss, homelessness, displacement, dispossession and forced relocation. The poems are precariously poised between the past and the present, acceptance and alienation, despair and hope, forgetting and remembering. They salvage unheard voices from non-existence and non-history. It is Sengupta’s rare, piercing voice, deeply empathetic, that invigorates it with testimonial veracity.

Issue 113 (Jan-Feb 2024)

-

EDITORIAL

- Sukanya Saha: Editorial

-

REVIEWS

- Aparna Singh: “The Crossings” by Chaitali Sengupta

- GSP Rao: “Why Didn’t You Come Sooner?” by Kailash Satyarthi

- Madhulika Ghose: “Tales of a Voyager (Joley Dangay)” by Syed Mujtaba Ali

- Sapna Dogra: “The DOG with TWO NAMES: Stories that Celebrate Diversity” by Nandita da Cunha

- Sreejith Kadiyakkol: “Journeying with India” by Y . Varma

- Subhash Chandra: “Mandalas of Time” by Malashri Lal

- Yamini S: “A Dark and Shiny Place” by Pragati Deshmukh