Sukanya Saha

Sukanya Saha

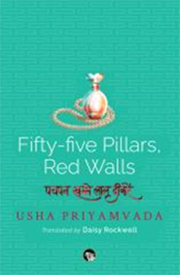

Fifty-five Pillars, Red walls | Fiction | Usha Priyamvada (Hindi original)

| Trans. From Hindi by Daisy Rockwell |

Speaking Tiger | ISBN: 978-81-944908-2-1 | pp 208 | 350

350

Painful realisations of raw human emotions

“That’s why I’m telling you that my life has already ended. I’m simply a means to an end” (96).

The revival of a classic and most importantly endeavoring to offer it in a language that is widely known, must be encouraged today for it being the exemplar of writing that won over its time. The book deserves accolades for the foresightedness of its author, Usha Priyamvada who upheld a question that was not cut out of the usual feministic wailings a prevalent inclination in her contemporary writings, despite it being essentially a women-centric narrative.

The monochromous projection of marginalized woman reeling under the grinds of patriarchy is not what one would confront here. It is rather a story of a woman who made conscious choices about entering a metaphorical black hole wherein chances of salvation would continue to diminish with each passing day. Usha’s book is still as relevant as it was nearly sixty years back from now when it was published in 1961. The translator, Daisy Rockwell’s arguments against the classic to be branded as Dated (7) are quite an engaging read. Daisy’s making Sushma’s story accessible to English language readers is commendable considering the need of the current college going crowd who swears by western classics to be aware of these rare gems which have been gathering dust on library shelves for decades. Such narratives are more relevant in postcolonial Indian contexts and most importantly relatable for their familiar settings and characters.

The Hindi title of the book Pachhpan Khambe Laal Deewarein would immediately transport one to the golden days of Doordarshan during 90s when the episodes of the drama based on this book were being telecasted. One may frown at its slow-paced dialogues and certain liberties the screenplay had taken though.

Usha’s female protagonist Sushma does not strike as another archetype of a woman who harbors and subsequently executes revolt post much (apparently) traumatic deprivations and societal/familial atrocities. Nor does she relinquish her worldly abode adding to the repository of the accounts of pains women have endured for decades. Sushma is an educated working woman, a professor, who is the sole breadwinner in the family. It is a typical family living in villages or small towns of India reminding one of the Hindi feature films of 1960s. There is an old, incapacitated father who is ever remorseful for being a daughter’s liability; a mother, for whom the eldest daughter is the only resource to cling to, a dependence that has turned her blind towards the latter’s psychic health. There are four younger siblings who look up to Sushma for their marriages and education.

The novel is its author’s maiden venture and does not indulge the reader in artistic intricacies. Reading such writings soothes your nerves because you neither need to depend over references to understand the contexts they portray, nor the circumstances in which characters find themselves are alien to you. There is a sense of profound grief that has wrapped all other emotions, analogous to Hardy’s adage, “Happiness is but an occasional episode in a general drama of pain”. Love and bliss occasionally ooze from crevices of the impenetrable density that engulfed Sushma’s persona. Even the portrayal of Sushma’s attraction for Neel is stroked with the guilt that haunts her.

“She wasn’t a carefree young girl. Her every action was scrutinized in detail […] She’d hurt him for no reason. She realized this but felt bound by the invisible ties of her reputation” (44-45).

Sushma, her colleagues, and her mother do not appear as symbolic existences of some abstract phenomena. They are what you understand of them after reading them sans any implications whatsoever about them being adumbrations awaiting an awe-inspiring theoretical exposition. Usha’s style and imagery are uncomplicated and that helped the book to bring out its essence, that is, a deep empathy towards Sushma’s bewilderment.

“Her mother was no longer worried about Sushma; all her attention was now focused on the smaller children. Sushma often felt neglected. She wanted her mother to try to understand her struggles” (28).

What stopped Sushma to marry as well as continue supporting her family is the question that lingers throughout the novel’s course and remains ruefully unanswered. There are pressing needs of her ailing father and siblings. The younger sister’s marriage has become her nagging mother’s only preoccupation so much so that the mother chooses to ignore Sushma’s love interest in Neel and enquires of Sushma about his prospects of marrying the younger sister. Such instances starkly lay bare the self-centeredness that drives humans living in poverty’s mortar and are being ground by the pestle of responsibilities.

“‘That boy who came to see you that day—couldn’t Niru get married to him?’” (134).

Sushma stifles her longing for a happily married life to provide for her parental home indeterminately. Hers is a dilemma that would suffocate for being trapped in life that is deliberately kept devoid of vents.

“It’s impossible for me to marry and leave my family with no support. I’ve prepared myself for such a life. If you go away I’ll imprison myself in those same ramparts again” (96).

Whatever the ideal age fixated for an Indian woman to get married, has passed for her now and her family’s obliviousness to the fact grows increasingly irksome to an empathetic reader. Perhaps the insecurities of her mother that her eldest daughter may abandon them once she gets her own household, yoked Sushma to that mill of domesticity and drained her off the vestiges of dreams for a future of her own. Father’s paralysis and demands of younger siblings have drowned her prospects of detangling herself from this cobweb ever in this lifetime.

“‘You wouldn’t understand, Neel. My father has always been very lazy. He just can’t get anything done. Mother pins all her hopes on me’” (83).

Sushma’s outbursts and her regrets following them, are the ebbs and tides of emotions that highlight the battles she fights with her own conscience in every clash with her mother. It is painful to read how she has molded herself into the understanding that she is living to pay for her parents’ failure, and protests are pointless.

“You must wonder what sort of a mother I have sometimes, but life has wrung her dry. Even though she’s my father’s second wife, none of her dreams have been realized. She takes out all her irritation and annoyance on the family. Her husband is weak, her daughter headstrong…” (96).

The point which such a dejected existence raises in reader’s mind is, where all this led her ultimately? Why has she alone been unquestioningly subjected to such burdens for a family which had a couple of more young members who could work to make the ends meet? She had to stoically suffer the pain of seeing her former lover now married and living a happy life.

“Sushma felt as though she was stuck in a swamp. She floundered, wanted to be saved, but sank deeper day by day” (133).

Sushma’s predicament is the outcome of prevalent illiteracy and poverty in rural India with large families. People underwent extreme hardships to just survive a day, let alone educating themselves and earning livelihood. Under such circumstances, if one member makes decent living, the responsibility of entire household is imposed on him or her. That member becomes a fulcrum who balances work and ever-growing demands of the family. Sushma’s mother’s disapproval after she resigns from her previous job, underlines how families could turn hostile if that sole life-sustaining source of income dries up and the gloomy fog of miserable future starts hovering around.

“…this job is very precious to me... ‘When I told my mother I’d resigned, she asked, ‘But what will happen to these children?’ Father had been sick the whole year… ‘Ma didn’t offer me any support…Every time she went out to sell a piece of jewellery, she looked at me as though I was the one responsible for all our suffering” (96).

Sushma could never wash her hands off from her responsibilities and push her family into dark to be consumed by the gaping hollow of uncertainties. Hence, she chose to drown her longings to keep her family’s life afloat. She takes pride in pursuing an academic career which made her independent by definition, “She felt as though she really had become someone. Respect for her had grown.” (20) Yet her independence had turned into a curse where she was pegged to the grinds of family, “How insubstantial was her good fortune, how hollow!” (129).

Usha has projected the weary and lonely Sushma convincingly. She represents a middle-class individual whose limbs are tied to the pulling strings of “desire, financial freedom and familial obligation” (5). The composite of fifty-five pillars and red walls of her college is her world from where there is no escape. This is her haven, where she has an identity and commands respect. This bricked enclosure reverberates and immerses her mute protests.

“Sushma liked the clarity of his eyes, the openness of his laugh. At this thought she regretted for the first time those lost years of her life. Those years had dissolved quietly into the daily routine of life and questions of livelihood, and now walls had closed in all around her—of frustrating obligations, of the importance of her status and of her family” (50).

With the entry of Neel, the narrative seems to take a pleasant turn. However, the quandary Sushma confronts after falling in love with Neel, is the message the author intends to uphold. Sushma had surrendered to her fate. Neel opened a window of that dungeon in which Sushma had confined herself. She lets her guards down and allows Neel in. Neel however found his love being reciprocated and turns hopeful about his future with her. There was nothing kept under garbs between them which would have lifted its ugly face to crush the blossoming of love. Neel was aware of Sushma being elder to him and her responsibilities. Neel’s mature handling of Sushma’s delicate feelings has been so artfully penned by the author. The transformations that took place rapidly in her were beyond her grasp. Neel’s presence uprooted her edifice of self-restraint and she soars. This soaring however ends with a crash landing when the blazing sun of societal obligations melts her Icarus wings.

“Sushma didn’t need a lover. She didn’t even long for a husband. But at times her heart sank for some reason, and she trembled under the burden of her responsibilities towards her entire family. And then she wished there were two more hands to lend her support; that there was someone to whisper to her in this silence” (50).

The simplicity of emotions renders this narrative its relatable quality. Neel evokes an empathy in the reader which is directly proportionate to the disgust Sushma’s mother raises being rather deliberately indifferent towards her daughter’s silent tears. There are occasions when the mother shows that she understands Sushma’s pains, but her such understandings are hollow and thus, inconsequential. Neither Sushma mustered any courage to confront her mother with her prospects of marrying Neel nor her mother seemed to be wary of the emotional turbulence Sushma was caught in. Mother was blindfolded by her anxieties for getting her second daughter married while people around her left no stone unturned in making her realize that she has been unjust to Sushma. It is extremely moving to read how Sushma constantly battles with her conscience and suppresses her feelings for Neel while pushing him away.

Overall, the novel is a realistic portrayal of Sushma’s dilemma, her mother’s conscious ignorance, Neel’s sincere love, and hostility of the society that does not approve of an adult woman’s claims to happiness. The genuineness in Sushma’s yearnings for Neel’s company and his readiness to tackle all challenges for her would haunt one. The nitty gritty in Sushma’s life as a college professor and hostel warden, viz. the carping malevolence of jealous colleagues on one hand and assiduousness of genuine friends on another, the misdemeanour of Sushma’s students, are wonderfully captured by the author. The novel is recommended to those who believe in simplicity in the rendition of human emotions, unadorned by prolonged static descriptions and fast-paced movement that navigates through painful realisations of raw human emotions.

Issue 97 (May-Jun 2021)

- Atreya Sarma U: ‘Handcuffed to Love’ by Yuktha Asrani

- Atreya Sarma U: In Conversation with Yuktha Asrani

- Atreya Sarma U: ‘Kashmir! Kashmir!’ by Deepa Agarwal

- Atreya Sarma U: In Conversation with Deepa Agarwal

- Chaitali Sengupta: ‘Trail of Love & Longings’ by Amita Ray

- GSP Rao: ‘Painting in the Kangra Valley’ by Vijay Sharma

- Namrata Pathak: ‘This Land This People – Rajbanshi Poems in translation’

- NS Murty: ‘Need a Bit of Freedom and Other Poems’ – Telugu poems by K Siva Reddy in translation

- Semeen Ali: ‘A Red-necked Green Bird’ – Tamil stories by Ambai in translation

- Sukanya Saha: ‘Fifty-five Pillars, Red walls’ – Hindi novel by Usha Priyamvada in translation

- Sutanuka Ghosh Roy: ‘Alleys are Filled with Future Alphabets’ by Gopal Lahiri

- Umesh Patra: ‘Sylvia – Distant Avuncular Ends’ by Maithreyi Karnoor