Soni Wadhwa

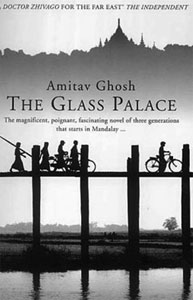

Outside in the Jungle: Narrating the Nation in Midnight’s Children and The Glass Palace

The increasing bulk of research on the study of nationalism from various

standpoints reflects a concern for the exploration of the way it operates and

the reasons behind its strategic survival. One of the ways nationalism gets

revealed is the realization that the proprietary rights of such a concept lie

with the Western or European world, to begin with. Secondly, texts like Nation

and Narration scrutinize different aspects of nationalism, especially the way

it gets insidiously defined with reference to other nations. Thirdly, Anderson

points out that nationalism seeks to unify heterogeneous communities/groups

with the help of tools like claim towards a common antiquity/history. This

paper intends to look at the way the novels in question (Midnight’s Children

and The Glass Palace) hint towards other perspectives for understanding

nationalism and one of them is in contrast with nature (or the jungle, to be

precise). The argument is that the two characters in the two novels get closer

to their selves while they encounter nationalism in the jungle; what draws

them to scrutinize their actions and relationship with their civilisational

milieu is a break from their ‘real world’ environment. It can be suggested

that the jungle becomes a site which could be another dimension to look at

when it comes to a nation’s discursive dissemination about itself – the nation

is not an entity independent of other nations around it, but it is also a

space that very often neglects the space of nature even within its ‘political’

boundaries. Hence the suggestion that the jungle is outside-in. Besides the

jungle, nationalism can be also seen as reflected in an individual’s

understanding of the nation. Both the jungle and the self tend to be seen as

the nation’s Other and when the two meet, a discovery (of history) takes

place. This paper attempts to chart out different implications embedded in

such a discovery with special reference to Bhabha’s introduction and Brennan’s

essay in Nation and Narration. While Bhabha talks about a possibility of a

‘recess’ in nationalism’s engagement with the self, the ruptures in the

nationalist narrative discourse serve to visibilize new avenues of

dissociating the self from it, while identifying those ruptures.

Bhabha’s argument begins with a discussion of similarity between nation and

narratives, highlighting the ontology of their “arche” as ‘impossibly romantic

and excessively metaphorical’ (Bhabha: 1), though it emphasizes the nature of

‘nationalist narrative (as) national progress, the narcissism of self

generation, the primeval present of the Volk’ (Bhabha: 1). The recurrence of

nation(alist) discourse as imbricated in collectivism becomes very telling on

the subservient position that a citizen/self/individual holds in the

nation-individual axiology. Bhabha’s point is, of course, well taken in the

context of discursive nature of this axiology. However, it is also interesting

to look at the same, foregrounding an individual(‘s) self as it reflects its

perspective on the nation at the most microcosmic level – the conceit of the

family being another reflection on the same. The suture of the private and the

public that Bhabha talks about, with reference to Hannah Arendt’s view, is a

step further from the nation-centered dissemination that may make passive

receivers out of the selves. The conceit of space, relevant for our purposes

here, is the third point in the discussion of such a dissemination, when

Bhabha refers to the notions of ‘heimlich’ and ‘unheimilich’ (Bhabha: 2). One

of the possible corollaries of such a situation may be that the pleasures of

the hearth … (and) terror of the space or race of the other’ (Bhabha: 2) very

readily gets absorbed for an intra-national situation, with an explicit focus

on the self on the one hand, and the nation-as-the-other, on the other side as

discussed above. The ‘pedagogical value’ of the ‘national objects of

knowledge’ (Bhabha: 3) and its ‘holistic representation’ may be suggestive of

(in the least) its irrational or arbitrary nature implied in the space of the

nation. The ‘narrative address’ that draws ‘attention to language and rhetoric

… (and, therefore), the conceptual object itself’ (Bhabha: 3) ignores the

graphic textuality of the space of nature that could be one of the spaces of

the Other constituting the ‘unheimlichness’ in the context of the

intra-national axis discussed above. This space of nature, especially, in the

postcolonial novels, I argue, becomes the frontier of the self-nation

negotiation, whereby an individual self engages with the nationalist narrative

dissemination and ‘alternative constituencies of peoples and oppositional

analytic capacities’ (Bhabha: 3). One of such constituencies and capacities is

‘nostalgia’, as Bhabha rightly notes. Nature, for instance, provides a

‘recess’ where the self may come to terms with her memory and reclaim itself,

outside the (nationalist) dissemination. It provides a new platform to

discover ‘”the unconscious as language”’ (Bhabha: 4), which Bhabha is in favor

of encouraging in the context of the ‘narrative knowledge’ that ‘maybe

acknowledged as ‘containing’ the thresholds of meaning’ (Bhabha: 4).

Interestingly, he also refers to the non-unified nature of the space or

‘“locality” of national culture’ (Bhabha: 4) but the foregrounding of the

collectivism in the form of ‘new People’ again does not allow easy

assimilation in our proposed axiology. The negotiation between ‘the political,

the poetic and the painterly’ is again all for the group(ed) identities. The

‘interruptive interiority’ and the ‘civil imaginary’ are linked with

‘feminisation of society’ (Bhabha, 5) which is very reminiscent of connotation

of exoticness associated with nature, as opposed to civility or civicness of

culture. Gillian Beer’s discussion of ‘land, and water margins, home, body,

individualism’ (Bhabha: 5) opens up the way for natural space in the

negotiation. The only disturbing issue is that ‘new places’ (Bhabha: 6) that

are to be explored for the purpose of negotiation seem to be unaware of

possibility of nature as such a site. The site of nature, I suggest, rings

with the fecundity of opening up new dialogues when considered again in the

context of the form of the narrative.

The purpose, here, is to demonstrate how a/the narrative self‘s descriptive

discussion of the nation is moulded to a large extent, by the ‘recess’ that

the self undergoes in nature, or in the jungle, to be more precise. The jungle

enters the narrative or the characters enter the jungle at the crucial point

in the novels Midnight’s Children and The Glass Palace wherein the putative

character undergoes a huge change in the understanding of the self and the

nation either through recollection or through realization. The background to

both the jungles is the war (of course, both real and metaphorical) and the

jungle becomes the site where the character happens to hide, or rather,

happens to choose to hide. The attempt, here, is to look at both the jungles

and the form of the narrative and the light that the interaction between the

both throws at the negotiation between the self and the nation. Such an

exploration involves the analysis of the description of the jungle that is

full of horror, the gothic element, darkness and therefore, the exoticness

(depending on the variable of magic realism). The intention is to theorize the

event of the jungle in act of negotiation with the nation as the Other, which

in turn, looks at the spaces outside it (including the ‘land and water

margins’) as the Other. Such an exploration, interestingly, highlights the

simultaneity of the intra- and inter- space of the nation that is not very

articulate about its position with regard to nature, and uninhabited and

uncivilized spaces. The purpose of invoking Bhabha and Bhabha’s invocation of

others was to prelude the debate with the context of the nation’s narrative

address that may provide a useful insight into the absence of the nation’s

non-address to the nature space that is both ‘outside’ and ‘in’ it (to invoke

Spivak).

Benedict Anderson’s sensitive exploration of nation as ‘imagined’ points out

the ‘imaginary’ (an adjective and a noun) nature of the narrative discourse of

the nation. However, the narrative imagination of a character in a novel needs

to be seen to have equal currency to make sense of the self’s understanding of

the nation’s narrative discourse. Saleem Sinai, for instance, is pulled

towards the recluse of the Sundarban forest, graphically narrated, with an

unstinting texture of the gothic. The forest is one of the borders India

shares with Bangladesh, problematizing the frontier-nature issue. Saleem

sniffs his way into the jungle, accompanied by his three friends. ‘The

sepulchral greenness of the forest’ (Rushdie: 432) is explored in all its

intensity in the adventure. Saleem uses expressions like ‘the night jungle

screeched’, ‘sucked it in’ (Rushdie: 433), ‘insanity of the jungle’, ‘terrible

phantasms of the rainforest’ (Rushdie: 434) and the list is quite long. Saleem

also says that ‘the chase which had begun far away in the real world, acquired

in the altered light of the Sundarbans a quality of absurd fantasy which

enabled them to dismiss it once and for all’ (Rushdie: 434). The idea that the

wilderness of the milieu begins to impact the ‘real world’ missions that

become ‘absurd’ invokes the age-old nature/culture debate with new

connotations of nation and nationalism, which are considered to be guardians

of civilization and culture. The jungle here is seen as forcing upon the four

men ‘new punishments’ (Rushdie: 435). The primitivism-or-back-to-the-nature is

a well demonstrated issue in the novel especially where even before entering

the jungle, Saleem turns into a man-dog and loses his memory; and quite

interestingly, the jungle seems to have given him his past (while his friends

are visited by animals with their ancestors’ faces). This interesting incident

of reclaiming the self happens in the ‘recess’ of the jungle that is

outside-in-the-border, figurative of the trope of liminality. The in-between

position of being in the frontier-jungle and of feeling the ‘real world’ as

absurd, yet regaining one’s genealogy, and of regaining everything except

one’s first name get highlighted against the absolute foundationalism of the

nationalist discourse (of the dictates of the senior military officers). The

night visits by ‘four girls of beauty’ (Rushdie: 439) whose ‘caresses’ felt

real enough’ (Rushdie: 439) make them increasingly transparent. This

transparency, though physical, is also symbolic of the emotional and

psychological aspects that are rendered opaque by several ideologies

(especially, of nationalism) in the process of civilization. Though the jungle

is hostile, it is also didactic for it has taught them several lessons, which

the four men forget once outside it. This is precisely where Edward Soja’s

argument of the ideologies being deeply imbricated in the space, comes in.

Timothy Brennan’s essay ‘The national longing for form’ engages with the

relationship between nation and the novel, and traces the history of such a

relationship. His discussion of the Third World literature is reminiscent of

Jameson’s argument that such literature is largely an allegory of nationalism.

Brennan focuses on ‘the nation-centeredness of the postcolonial world’ (Bhabha:

47) when he says:

In fact, it is especially in Third World fiction after the

Second World War that the fictional uses of ‘nation’

and ‘nationalism’ are most pronounced. The ‘nation’

is precisely what Foucault has called a ‘discursive

formation’ – not simply an allegory or imaginative vision,

but a gestative political structure which the Third World

artist is consciously building or suffering the lack of.

‘Uses’ here should be understood both in a personal, craftsman like

sense, where nationalism is a trope for such things as ‘belonging’,

‘bordering’, and ‘commitment’. But it should also be understood as the

institutional uses of fiction in nationalist movements themselves.

At the present time, it is often impossible to separate senses’

(Bhabha: 46 – emphasis original).

The two novels in question here critically deal with these two issues – the

‘commitment aspect in terms of loyalty that is expected form the protagonists

and the ‘institutional’ aspect in the sense of the agency of military that

plays an explicitly defining role on the borders. Saleem’s commitment is torn

apart between India and Pakistan, or between Pakistan and Bangladesh, when he

is in the third space of Bangladesh border where the entire conflict is

brought into play. The similar situation seems to apply to Arjun’s condition

in The Glass Palace where his ‘belongingness is problematised – does he belong

to India, which has not yet become a nation (and quite ironically, this fact

does not interfere with the production of nationalist discourse about itself)

or to his English masters? The problem is intensified when it is considered

that the ‘recess of jungle that happens the narrative is outside-in Malaya

vis-à-vis India, and thus, the third space enters in. Both the characters

encounter the process of nationalist discourse formation, twice removed from

their spaces.

The trope of ‘allegory’ or ‘imaginative visions’ seems to be indispensable

with the so-called Third World literature. Various critics have demonstrated

the presence of family as a trope whose history is a microcosmic version of

its national counterpart. The allegory therefore functions as a narrative

device that constructs the national history through the personal memory and

heavily draws on the imaginative of fictive resources of the general imaginary

that is quite open to observation. Allegory works differently in both the

novels since both talk about different periods in colonial/neocolonial history

and are written in different moments of postcoloniality. With Rushdie’s novel

that uses magic realism (and a whole mélange of genres), allegory boils down

to a direct corresponding relationship between a nation and a child. It is

therefore not a correspondence between a family and a nation in the broader

sense that would accommodate the entire family from the beginning to the end.

Where the novel is not magic realist, it is melodramatic (among many other

things). For instance, it is interesting to note that the novel would have

been looked at another piece of magic realism, the then-latest (or

not-so-latest) buzzword in literary writing. It would have been a very

palatable work if Padma (who is generally seen as readers’ consciousness) had

been absent, along with her feeling of seeing all that Saleem narrates from a

scandalized perspective. The genius of the novel, therefore, lies in its

critique of itself on every level of palimpsest; it is a work that is

antifoundational in every sense, even in its form. Seen in this context, the

allegory motif gets disturbed since we do not know for sure the position of

the character in ‘recess’. Is Saleem Sinai really Saleem Sinai? Or, is he

really Shiva? These nuances of disruption in identity heighten the subaltern

condition of his self. Ghosh, on the other hand, holds on to a more or less

realist mode of expression, chronologically developed, with an emphatic

engagement with the process of history and a proper focus on the use of many

families from many spaces. The narrative here is not at all representative of

all families’ struggle in the Burmese independence struggle in the narrative.

The genealogies that are unfolded are not correspondingly/allegorically

interlinked with the nations in the symbolic sense. This realist device is not

anti-foundational, but a process of confronting the foundations, proceeded by

its articulation (in the army scenes, as witnessed by Arjun).

The element of ‘gestative political structure’ that Brennan talks about, once

again, sensitively describes the need for ‘recess’ in the two narratives. In

Rushdie’s novel, the nation that is newly made emerges along with Saleem’s (mis)adventure

in the jungle, while in Ghosh’s novel too, Burma is being made while Arjun

also is in the jungle and India would win her independence later. Though the

India in Midnight’s Children is already made, in the sense of decolonization

and its aftermath, it remains “a myth” (as Rushdie reiterates in the novel) –

in the sense that its ideals of independence have not been realized and also

that we have not left it behind with the past. Thus behind-with-the-past chronotrope becomes forward-in-the-future in

The Glass Palace while Arjun

attempts to come to terms with the dilemma of his identity. The gestation that

involves him contributes to the formation of the nation. These gestations in

the jungles become the space between the cosmopolitan and the subaltern voices

that the nationalist discourse needs to deal with effectively. Brennan quotes

Bruce King:

“Nationalism is an urban movement which identifies with the rural areas

as a source of authenticity, finding in the ‘folk’ the attitudes, beliefs,

customs and language to create a sense of national unity among people

who have other loyalties. Nationalism aims at … rejection of

Cosmopolitan upper classes, intellectuals and others likely to be

Influenced by foreign ideas” (Bhabha: 53).

Arjun and Saleem come from urban backgrounds, are reduced to the state of subalternity since their lives and families are devastated by the existing political situations, but they are able to visibilize the psychological struggle that they are going through, in the jungle. Both gain the selves, the very idea of which is at loggerheads with the concept of a nation (which is communal).

Brennan tells us that Walter Benjamin saw the genre of novel increasingly degenerating because of its vulnerability towards the encroachment of information. However, Brennan gives the example of Third World fiction that has not proceeded in the direction prophesied by Benjamin because it

1. elevates memory by making an effectively regenerative use of it

2. It ‘moralizes recent local history sketching out known political positions’ (Bhabha: 56) and,

3. It has borrowed ‘from the miraculous’ through the device of ‘magic realism’, not falling prey to invasion of information.

The three points in defence of the neocolonial or postcolonial novel are to

some extent also three paradigms of the jungle in the novels concerned here.

The way memories are rekindled to awaken the personal/selfed side to the

militant/militaristic role played in the political has already been pointed

out. The second point about moralizing need not imply orthodox didacticism

implicit in many allegories but the way a certain political position has to be

taken in one or the other form to escape any kind of tyranny. Attributing a

national correspondence to a personal event does not help in exposing the

existing political failure. While Saleem takes lessons from the jungle, Arjun

becomes bolder to resist the dictates of the English rulers. The point of

magic realism applies only to Rushdie to highlight the importance of the

miraculous that poses danger to the self (seen as a threat) from the

super/natural and speeds up the need to rush back with the regained memory.

According to Brennan, the Third World fiction, located in the neocolonial

moment critiques the politics of neocolonization and “exposes the excesses

which the a priori state, chasing a national identity after the fact, has

created at home” (Bhabha: 58). The jungle helps Saleem realize the absurdity

of the real world – similarly, a distanced position helps Arjun decide who he

is and whom he considers his Other. Moreover, to counter the myth of the

nation, Saleem produces the countermyth of M.C.C. and Arjun begins to resist

the myth of loyalty.

For Brennan, any attempt to critique the political dogma of nationalism

sometimes results in exile of the novelist. About Rushdie he says, that while

exploring ‘postcolonial responsibility’, ‘he treats the heroism of nationalism

bitterly and comically because it always seems to him to evolve into the

nationalist demagogy of a caste of domestic sellouts and powerbrokers” (Bhabha:

63), and that writers like Rushdie ‘have been well poised to thematize the

centrality of nation-forming while at the same time demythifying it from a

European perch’ (Bhabha: 64). This topos of exile aptly applies to Arjun and

Saleem, Ghosh being a diasporic like Rushdie. The novelty of his

demythification of India lies in the way he has not placed India at the center

of the exploited peoples; on the contrary, he brings out the Indians’ position

as ‘mercenaries’ and colonizers with reference to their economic invasion of

Burma, being referred to as ‘kalaas’. The critique does not question the

mimicry class of Indians alone that sides with the British, but also the way

Indians exploit the Burmese economy.

Let us return to the issue of the exile. The topos of exile of the characters,

not the authors, in the jungle and the effects of exoticness and reclamation

caused by it could be largely attributed to “violent geographics” that David

Punter talks about. (Punter: 29). Punter analyzes the way nature has been

shown to be exploited in several postcolonial novels and throws light on the

way nature has been shown to be exploited in several postcolonial novels and

throws light on the way nature has been harmed in the process of colonization.

He draws attention to colonization’s Kafkaesque ‘bureaucratic Gothic’ while

dealing with Coetzee’s Life &Times of Michael K (Punter: 33). In the context

of the novel, he says: ‘…despite all the reterritorializations, the

partitions, the redrawing of boundaries for imperial convenience, something

rocklike remains, something that has survived the violence and exploitation

and thereby demonstrates the salving possibility that all can be made whole

again, that new maps can be drawn on fresh paper, that the legacy of

domination can be erased’ (Punter: 34). It is in this sense that the violation

caused to the geographics can be dealt with, or in a way that has already been

defeated by impenetrability of the natural surroundings that cannot be totally

colonized. Perhaps this retention of some kind of purity by nature can help

spaces like the jungle become sites of an individual’s self and the ideology

that is imposed upon her. Saleem’s discovery of his memory and Arjun’s

realization of his self, nuance this space with a sense of strong support that

may be useful to begin again. At a later point, Punter says: ‘…geography

itself is dependent o power’ (Punter: 35) that resonate Soja’s ideas. Saleem’s

jungle and Arjun’s plantation are highly charged with political and economic

dependence – since the jungle is seen as frontier because of the political

arrangement of the putative nations (decided upon by the British) and the plan

is an organized space to harness natural resources for economic ends and at

the same time, it is an organized hideout of the Indian Independence League.

Moreover, Punter also says, ‘Geography claims its fixities and certainties;

but below this there continues a world in which a radical displacement has

paradoxically taken the center of the stage’ (Punter: 37) and that space

refers to that of identity that is rendered unstable in the process of moving

from on geography to another, where the event of deracination affects an

individual the most.

While jungle is the source of horror in Midnight’s Children, it is relatively unharsh in

The Glass Palace, with a touch of anonymity that does not ascribe

to the jungle a specific air of hostility. Ghosh describes the jungle as:

‘Sound appeared to travel and linger without revealing its point of origin. It

was as though (Arjun) had woken up to find himself inside an immense maze

where the roof and the floor had been padded with cotton wool’ (Ghosh: 388).

The jungle in the novel, interestingly, is also a site of war, which does not

totally let it remain undiscovered and unharmed like the Sundarbans. The

jungle is described with strong resonance of claustrophobia - ‘geometrical

maze’, ‘padded cage’ and so on. Since it is a war front, it delivers the

message of Indian Independence League, which begins a series of self-doubts in

Arjun’s mind. While Rushdie’s description of the jungle is characterized by

horror, there is very little description in Ghosh. Instead, there is a

constant sense of debate regarding issues of allegiance and traitorship, of

similar areas dichotomized by civilizational ideologies. Without taking any

explicit sides, the jungle sensitizes Arjun towards the human vulnerability

that cannot be privileged to, or overcome by, any one kind of nationalism. In

this sense, the jungle stands for human disillusionment with the civilization

around the national space. The cruelty of ideologies of various nations at war

with each other invades the jungle with it s accoutrements of war. For

instance, Arjun is shocked to see tanks in Malay, which was not ‘a tank

country’ (Ghosh: 395), which leaves him ‘stranded in the middle of the road,

like a startled deer’. Suddenly he was inside a long tunnel of greenery, his

feet cushioned by a carpet of fallen leaves’ (Ghosh: 396). The comparison with

‘a startled deer’ and the comfort of a ‘cushion’ or a ‘carpet’ reveals how

accommodating this jungle is. However the same jungle gives him ‘this chaotic

sensation of collapse in one’s head, as though the scaffolding of responses

implanted by years of training had buckled and fallen in…’ (Ghosh: 397). The

situation is similar to Saleem’s – on the one hand, there are ‘caresses’ of

the jungle and on the other, thee is a painful process of reviewing one’s

past. Nature raises difficult questions for Arjun: ‘He thought of the heavy,

gilt-framed paintings that hung on (the club’s) walls, along with the mounted

heads of buffalo and nilgai; the assegais, scimitars and feathered spears that

his predecessors had brought back as trophies from Africa, Mesopotamia and

Burma. He had learnt to think of this as home, and the battalion as his

extended family – a clan that ties a thousand men together in a pyramid of

platoons and companies. How was it possible that this centuries-old structure

could break like an eggshell, at one sharp blow – and that too, in the

unlikeliest of battlefields, a forest planted by businessmen?’ (Ghosh: 397).

Like Saleem, Arjun discovers a third space that waits to claim him out of the

two warring nations. Such a claim reaches Arjun through a realization that his

victory and his efforts in the victory of the British would go unacknowledged

now matter how hard he tries. Hardy points out: ‘…you’re fighting against

yourself… Am I being tricked into pointing (the gun) at myself?’ (Ghosh: 406).

He also points out ‘…it’s when you’re sitting in a trench that you realize

that there’s something very primitive about what we do’ (Ghosh: 407).

Of course, one may argue that while Saleem is disillusioned with the discourse

of nationalism, Arjun finds his way into it, by contributing to when he begins

to participate in the League activities. There is obviously a difference

between the nationalisms presented in the two cases – Saleem is located in the

neocolonial moment, while Arjun in the pre-colonial. The fact that the

nationalism (the Indian nationalism) was not an achieved reality with a

geographical space attached to it through political sanction does not make the

nationalism (the Indian nationalism) he confronts and chooses to side with

invalid or non-existent. On the contrary, his nationalism is of a more crucial

kind – an insidious structure that claims his loyalty without being

materialized in the form of decolonization; or rather, it absorbs him in the

process of decolonization. For Saleem, the jungle is a horror and, at the same

time, a connection with the past. For Arjun, it is a site of oblivion (Ghosh:

419) but saturated with new distinctions that come to him gradually – like

that of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ masters. Arjun recognizes that such a choice is not

choice at all. To choose one is to lose touch with what is human. Kishan Singh

points out to him ‘… all fear is not the same. What is the fear that keeps us

hiding her, for instance? Is it a fear of the British? Or is it a fear of

ourselves, because we do not know who to fear more?’ (Ghosh: 430). These

engagements with distinctions make Arjun realize that ‘… his life had somehow

been molded by acts of power which he was unaware….Everything he had ever

assumed about himself was a lie, an illusion’ (Ghosh: 431)

Ghosh does not seem to take any sides between India, Burma and the British. In

a style that is typical of him, he voices various conflicts that emerge in a

human being’s mind while moving from one space (of ideology) to another or

while being affected by various debatable perspectives. His critique of any

kind of partisanship lies in the way he theorizes every perspective by laying

it bare. On the other hand, Rushdie is vociferous in his diatribe against the

empire and the neocolonial condition where he is trying to identify a specific

agency in the conflict. Confrontation (brought about in the jungle) in both

the novels happens in the climax when the necessity of a resolution is at its

peak. Speaking in the sense of structures, the jungle is the climax that helps

to survive the discourse of nationalism (either by exposing its hollowness as

in Saleem’s case, or by highlighting the human agency that can help to

construct it as a means to end the slavery, in Arjun’s case). The idea of

refuge outside the space of the nation, in the space of the jungle inevitably

leads us to the question of maps. An almost cartographic engagement with

description of places in both the novels brings alive a sense of perpetual

overlapping, occlusions and inclusions that involved in the human beings

related to one another. The suggestion here is that nature is that because of

this outside-in-ness is a third space between the cosmopolitan attitudes

towards nation (that seek to defy any kind of imposed authority because of

being elite) and the subaltern condition (that is seen as a passive reception

ground for the downward movement of the dictates of nationalism) does not

intend only to introduce just another schematic to demonstrate a way out of a

binary opposites, but also to explore the way ideas reciprocate the

ideological spaces (like nationalism) with a fecundity that seeks to struggle

with a parochial claim for different kinds of belongingness, or a feeling of

belonging that deceptively co-opts individuals against their interest or

maliciously interferes with their lives.

References:

1. Brennan, Timothy "The National Longing for Form", Nation and Narration:Post-Structuralism

and the Culture of National Identity, ed by Homi Bhabha London: Routeledge,

1990

2. Ghosh, Amitav The Glass Palace London: Harper/Collins, 2000

3. Jameson, Fredric "Third World Literature in the Era of Multinational

Capitalism" Social Text Fall 1986

4. Punter, David Postcolonial Imaginings: Fictions of a New World Order

Edinburgh University Press/Rowman and Littlefield, 2000

5. Rushdie, Salman Midnight's Children London: Cape, 1981

6. Soja, Edward Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical

Social Theory. London: Verso Press, 1989.

7. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty Outside In the Teaching Machine London: Routledge, 1993

Issue 40 (Nov-Dec 2011)

- Charanjeet Kaur – Editorial Comment

- Lakshmi Menon – In Conversation with Sneha Subramanian Kanta

- Ramesh K – In Discussion with Ramesh Anand

- Thachom Poyil Rajeevan – In Conversation with GSP Rao

- Lalima Chakravarthy – Discourse on Diaspora

- Mujeeb Ali Qasim – ‘A House for Mr Biswas’

- Samina Azhar & Vinita Mohindra – Marathi Dalit Literature

- Sanjukta Dasgupta – Poetry of Transtromer

- Soni Wadhwa – Narrating the Nation